10 Reasons Dating Apps Are Screwing You

You hate it. You need it. That tension is the whole story.

Today: Dating apps digitised dating, turned desire into a measurable signal and then sold access to attention. The apps don’t just frustrate people; they produce disappointment, gendered imbalance, ghosting, and low trust as standard outputs, while queer users often stay because for them the app isn’t a vice, it’s required infrastructure.

You open the app with a flicker of hope that now feels like a compulsive superstition. Ten minutes later, you don’t feel like a person, but a line item.

Consider the archetypes of the desirability market:

There is the heterosexual man doing exactly what he was told: decent lighting, a bio suggesting a pulse, polite openers that die on delivery. For him, the app is a mausoleum of silence where he starts to suspect he doesn’t actually exist, at least not in the only currency the platform recognises.

Then there is the heterosexual woman who showed up despite the stories people say about these apps, only to be met with an industrial firehose of entitlement: unsolicited nudes, men who treat a “no” like a negotiation, and the little punishments that arrive when you decline. For her, the app is a high-stakes escape room where the exit is blocked by a creep holding a gym mirror.

If you’re queer, the luxury of a “digital detox” often doesn’t exist. The app isn’t a hobby, it’s the main door. You learn to tolerate hyper-objectification, status sorting, and the casual cruelties of the marketplace because the alternative isn’t a meet-cute in a bookshop, but romantic exile. For many queer people, opting out isn’t an option.

So why do we claim to hate these platforms, yet keep them on our home screens like a toxic ex with shared custody of our self-esteem?

To understand why we remain entangled in a system that makes us miserable, we have to look past the UI and into the architecture. Here are the ten structural ways these platforms have re-engineered intimacy into a market you were never meant to beat.

1) The app lets you reject yourself with data.

Dating apps don’t simply deliver rejection. They also deliver feedback (counts, gaps, silence) and the human brain does what it always does with feedback: it turns it into a story about you.

Offline, a bad date is contextual: someone wasn’t your type, the vibe didn’t land, you misread a signal. On the app, the experience becomes repeatable and quantifiable: you can refresh it, you can watch it stall, you can feel your “demand” drop with no explanation you can name. That’s the psychological shift: rejection stops being interpersonal and starts feeling like a market condition.

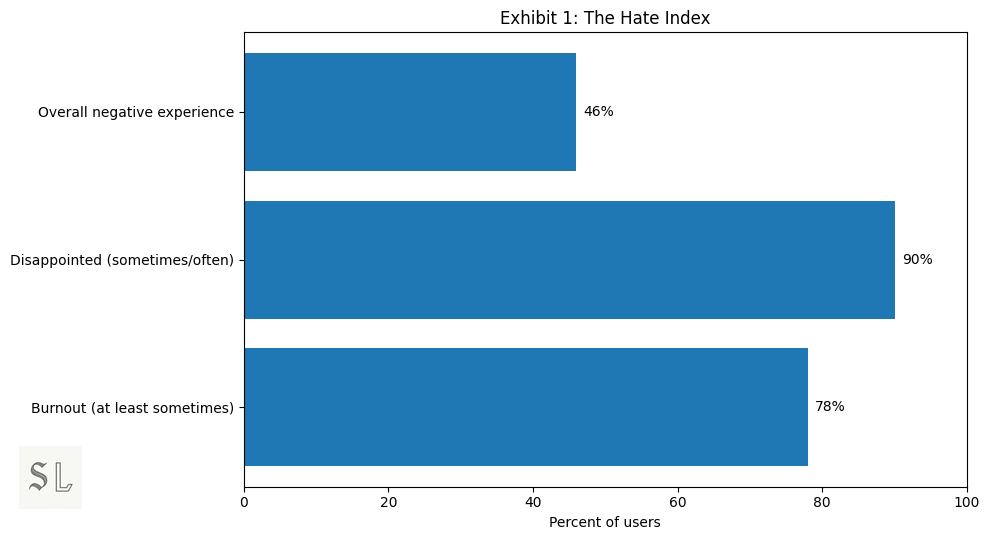

That’s why the feelings people report don’t read like ordinary dating disappointment. In U.S. survey data, 46% of users describe their overall experiences as negative. Among current/recent users, 90% report feeling disappointed sometimes or often. A separate (less rigorous, but consistent) survey reports 78% burnout. Those aren’t edge cases, but a category emitting a steady low-frequency hum of disillusionment.

The clincher is where the insecurity attaches: not to “I met the wrong person”, but to the numbers. In the same research pack, 55% of users report feeling insecure about their message count. Problem is, message count is not romance. It’s quite literally a proxy. Yet it becomes the mirror, because it’s the only mirror the platform reliably provides.

The language people use to describe the experience is correspondingly visceral: humiliating, soul-sapping, dehumanising, tedious, addictive, a necessary evil.

That’s the vocabulary of something that doesn’t just fail to deliver love, but actively corrodes the conditions under which love is possible.

2) The swipe compresses you into a signal.

Attraction used to be inconvenient in the way all human things are inconvenient. It happened in rooms, at tables, in motion, sometimes when you were in another relationship. It was built out of voice, timing, smell, humour, social context, how someone treated the bartender, how safe you felt standing next to them. It was rarely clean. It was rarely instant. It was rarely certain.

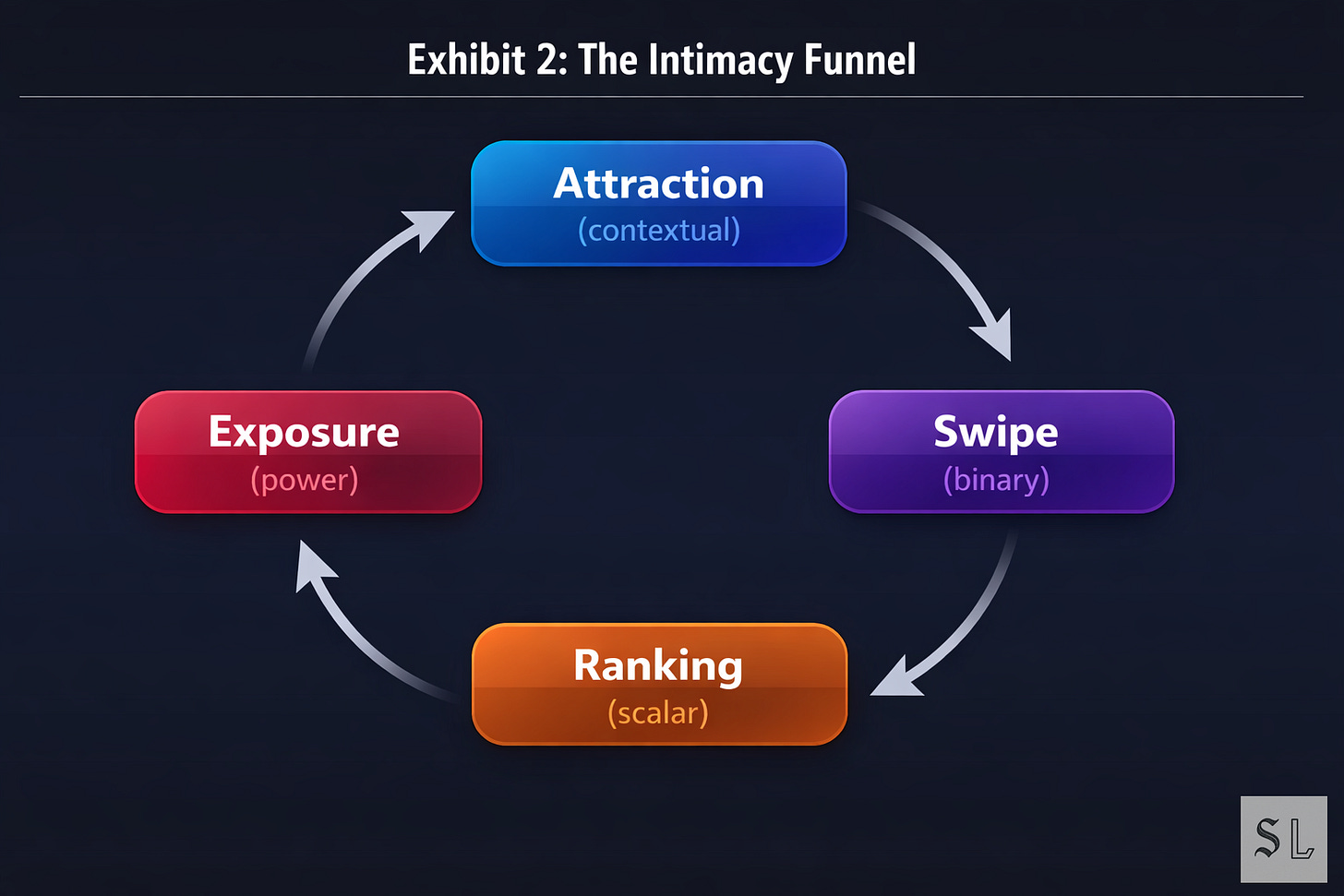

Then the apps arrived and did what platforms always do: they took something thick and living and made it trackable. The swipe is the core invention. A single, frictionless action that collapses a person into a binary outcome. Yes. No. Next. That binary is then treated as data, not only about who you like, but about what you are. Because once you can record desire at scale, you can model it, rank it, optimise it, monetise it.

In this setup, context, voice, timing, social accountability, safety and the subtlety of “maybe” (the most important category of early attraction) gets compressed out in the process.

What survives are photos, prompts, a handful of self-branding signals and whatever your nervous system can decide in 1.7 seconds while you’re half-bored and slightly lonely.

This is not a neutral trade off. Once people become swipeable, they become comparable. Once they become comparable, they become rankable. Once they become rankable, they become governable by whatever the platform wants to maximise.

The swipe doesn’t merely express preference. It trains the system that shapes preference. It teaches you what “works” in the marketplace, then quietly punishes you for not becoming it. Gym lighting. Same angles. Same ironic prompt cadence. Same algorithm-friendly version of “personality”.

You can feel the outcome everywhere: the flattening of taste, the convergence of presentation, the creeping suspicion that you’re scrolling through the outputs of a sorting machine, not an actual, potential match.

We turned flirting into input data, and then acted surprised when the whole experience started to feel like a dataset.

3) Desire doesn’t survive measurement intact.

Dating apps instrument desire, and once desire becomes measurable, it becomes deformable.

Some of the scoreboard is obvious: matches, likes, message volume, reply gaps, the little dopamine blips the interface drip-feeds you. Some of it is hidden: the allocation layer (who gets shown, when, how often, to whom). Either way, the lived experience converges on the same conclusion: your desirability has a number, even when the platform keeps the number off-screen.

That’s where description mutates into judgement. Not because users are irrational, but because the product is built to make the inference feel sensible. When your inputs are effort and vulnerability, and the outputs are silence or scarcity, the brain doesn’t file it under “random distribution dynamics.” It files it under me.

A systematic review finds dating app use is associated with negative body image outcomes in roughly 86% of studies and negative mental health outcomes in roughly 49%. Association isn’t destiny (some people arrive with insecurity, some acquire more of it) but the direction is hard to ignore: a measurement regime wrapped around desirability correlates with harm.

Desire doesn’t survive measurement intact. Once you can count being wanted, you start negotiating with the count, and the count steadily replaces the person.

4) Women drown; men starve. Both call it “dating”.

Despite being on the same app, heterosexual men and women are living inside two different psychological climates, each convinced the other must be exaggerating.

For many women, the issue is volume: too many people want something, and a meaningful fraction arrives laced with entitlement, threat, or contempt. Pew’s own breakdown captures the blunt shape of it: 54% of women say they have felt overwhelmed by the number of messages they receive, versus 25% of men.

Overload turns selection into a defensive posture. It also creates a second, nastier paradox: attention can be constant while desire still feels absent, because the attention is often low-effort, transactional, or explicitly sexual. The research also flags that 56% of women under 50 report receiving unsolicited sexual images, which makes the “inbox” feel less like possibility and more like exposure.

For many men, the problem is a different kind of humiliation. The app turns courtship into a scarcity environment where effort frequently produces silence, and silence starts to feel like a judgement about existence. Go back to the same Pew data point (40% of men say they’ve felt insecure because of the lack of messages they receive), and now layer in the structural imbalance of Tinder in particular. Reportedly, men outnumber women by roughly 3:1 in some markets. What’s simple basic supply and demand within the app starts feeling like personal failure.

Then the platform does what platforms always do: it converts these two experiences into resentment that can’t resolve itself. Men see women as sitting on a pile of options and conclude women are cruel, picky, or spoiled. Women see men behaving badly at scale and conclude men are predatory, unserious, or unsafe. Both stories contain enough truth to be emotionally satisfying, and enough distortion to be politically poisonous.

5) Ghosting is the signature behaviour of a low-accountability market.

Ghosting thrives in environments where reputations don’t travel and ambiguity can be endlessly scaled. In the offline world, vanishing carries a cost: awkward run-ins, mutual friends, a social memory that follows you. On apps, you can disappear with one thumb and suffer nothing but another profile.

When the pool feels infinite and exits are frictionless, people become interchangeable. The platform trains you to treat strangers as disposable inputs in your personal optimisation loop: swipe, match, chat, stall, replace. It starts as “keeping your options open” and ends as a culture where basic closure feels like an unnecessary extra feature.

The prevalence reflects how normalised this has become. Research says 62% of active users report having been ghosted. Think of that at scale. This is a baseline behaviour; the natural output of a system where the easiest way to end anything is to pretend it never existed.

And because it’s not explicit rejection, ghosting lands differently. A “no” has edges; you can metabolise it. Ghosting is a blank space your brain fills with self-blame. It turns someone else’s avoidance into your identity problem.

6) Harassment is the trust tax you pay to participate.

Every market has a hidden fee. In dating apps, it’s trust.

Harassment, scams, fake profiles, sexual entitlement, and the casual cruelty of strangers are the predictable cost of running intimacy through platforms built for scale. When you lower friction and raise volume, you increase “matches” alongside increasing the number of bad actors, the number of misfires, and the number of interactions that feel less like connection and more like exposure.

In U.S. survey data, 48% of users report encountering at least one form of unwanted behaviour (unsolicited sexual images, persistent contact after saying no, insults, threats). That number is staggeringly high for a product whose core promise is “helping people meet”. A platform that makes half its users deal with harassment are running a low-grade risk environment and marketing it as dating.

Then comes the second layer of the trust tax: users don’t believe the platforms are containing the problem. In the same research pack, only ~20% think apps do a good job removing fake profiles, while ~40% think they do a bad job. That perception matters as much as the underlying reality, because trust isn’t a nice-to-have in intimacy. To be human means trust is the substrate. Without it, people stop behaving like humans and start behaving like threat models.

Harassment and fakery trigger adverse selection: the most sincere, high-intent users leave first. The pool becomes more cynical, more defensive, more transactional. Everyone learns to withhold, to assume bad faith, to keep one foot out the door. The market becomes efficient at generating engagement and brutally inefficient at generating anything you’d recognise as closeness.

7) The tragedy of the swiping commons.

In any shared resource, rational individuals can destroy the collective outcome. The classic example is a pasture: each farmer adds one more cow because it benefits them personally, until the pasture collapses. Dating apps built the same structure out of attention. Everyone takes the rational move. The ecosystem still dies.

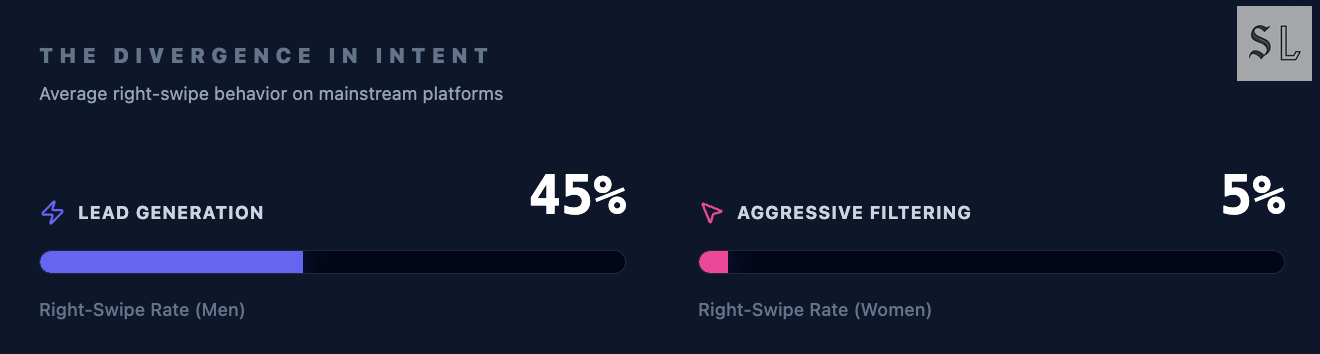

Start with the individual logic. If you’re a man on a mainstream app and your match rate feels like one in 130 swipes, you don’t respond by becoming more discerning. You respond by becoming statistical. You start swiping right on volume (“spray and pray”) because effort without output teaches you to stop treating this like courtship and start treating it like lead generation. (Research puts men at roughly 45% right-swipes.)

That mass-swiping doesn’t create more love, just more noise. Women’s inboxes fill with low-signal attention: half-interested matches, messages sent to ten people at once, men who didn’t read the profile and don’t care to pretend they did. The rational female response to overload is defence: filter harder, narrow faster, swipe right less. (The same cited figures put women at roughly ~5% right-swipes).

So the platform becomes an arms race where both sides are responding intelligently to the incentives and everyone ends up worse off. Men swiping more aggressively makes women more selective; women becoming more selective makes men swipe more aggressively. The feedback loop tightens until the only viable strategy is optimisation.

Profile SEO takes over. Gym pics, the same angles, the same prompt cadence, the same curated “I am fun but emotionally safe” template. You don’t present yourself; you A/B test yourself. The brief flags this as second-order optimisation: individually rational, collectively corrosive.

8) Late-stage extraction turns persistence into profit.

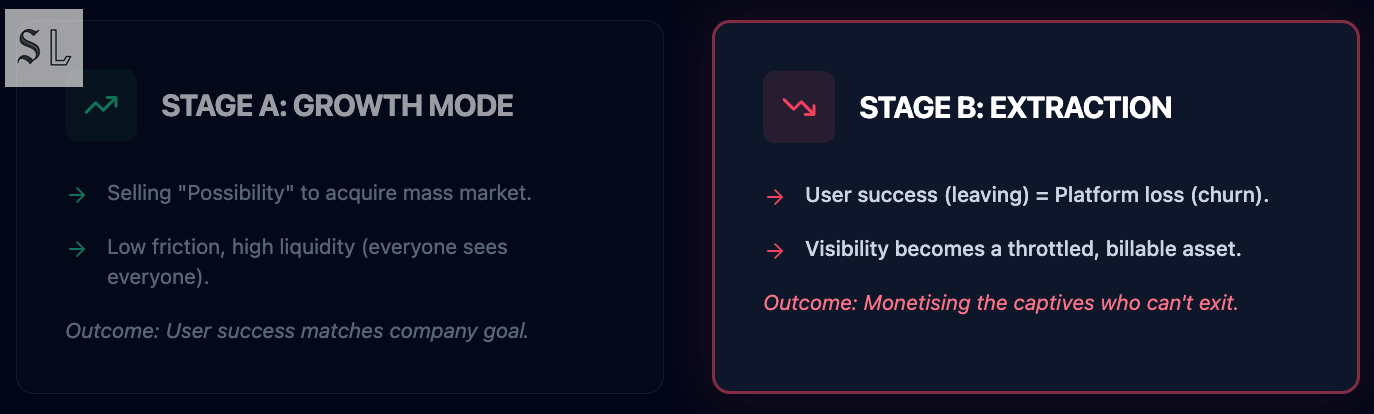

In growth mode, dating apps can pretend they’re selling possibility. In maturity, they have to monetise reality. When user growth slows and churn rises, the product stops being “matchmaking” in any romantic sense and becomes something colder: revenue optimisation on a captive pool of returners.

The financial tell is right there in Match Group’s numbers. In FY2024, total paying users declined by roughly 5% (to ~14.9M on the year), while revenue per payer rose by roughly 8%. Quarter-end payers were ~14.6M, which is why that figure keeps showing up. Fewer people are paying. The people who remain are paying more. This is a simple extraction curve.

Then zoom in on Tinder, the category’s flagship. Payers down roughly 7%, revenue flat or slightly up. That pattern has one clear implication: the platform is shifting from growing the pie to mining the survivors. They are squeezing more value out of the users who can’t quite leave, the ones still hoping the next swipe will redeem the last month.

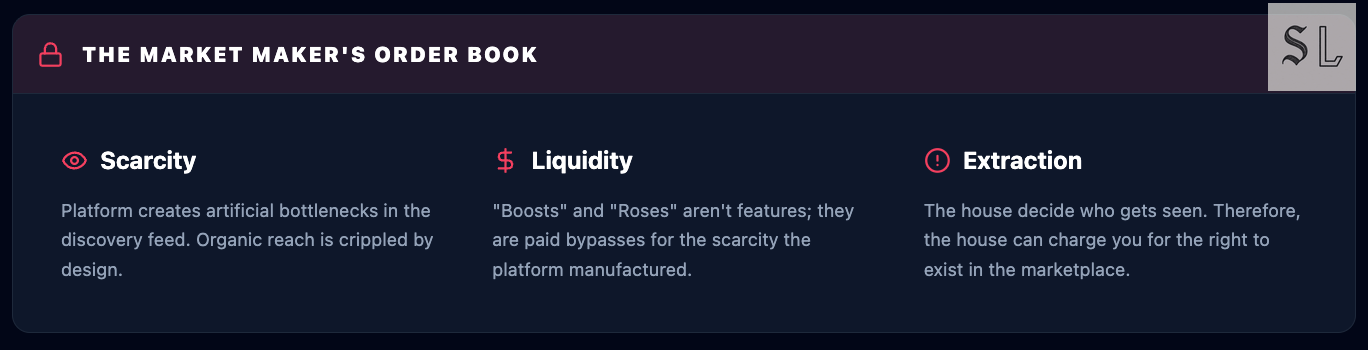

If the app’s cleanest outcome is that you meet someone and disappear, churn is success for you and loss for them. So the business has to find other ways to win: premium tiers, price discrimination, and, most importantly, selling visibility inside the market it controls. Because once distribution is the product, scarcity becomes billable.

“Boosts”, “Super Likes”, premium queues… these aren’t cute add-ons. They’re paid liquidity in a marketplace where the platform controls the order book. The structure is hard to miss: when the house decides who gets seen, the house can charge you to be seen.

9) Gen Z is walking away.

Dating apps had their moment: the early thrill of infinite possibility, the sense that romance had finally been made efficient, modern, scalable. Then the morning after.

In Western markets, especially, the cultural mood has shifted from “this is how you meet people now” to “why does this feel like unpaid labour?” The interface is losing legitimacy.

The cleanest signal is in the UK, where regulator-linked reporting shows the major apps shedding users year-on-year. Tinder is down roughly 600k, Bumble down 368k, Hinge down 131k from 2023 to 2024. This consistency across all three major players illustrates a cohort-level retreat from the category’s core promise.

Then comes the sentiment signal from the US: 79% of college students reportedly don’t use dating apps regularly and prefer meeting in person. You can argue about methodology, samples, hype cycles. You can’t argue with the direction of travel: younger users are increasingly treating the swipe feed as something slightly embarrassing, like smoking, or counting calories, or arguing with strangers on Facebook. An outdated habit from a previous internet.

10) The queer paradox: infrastructure vs entertainment.

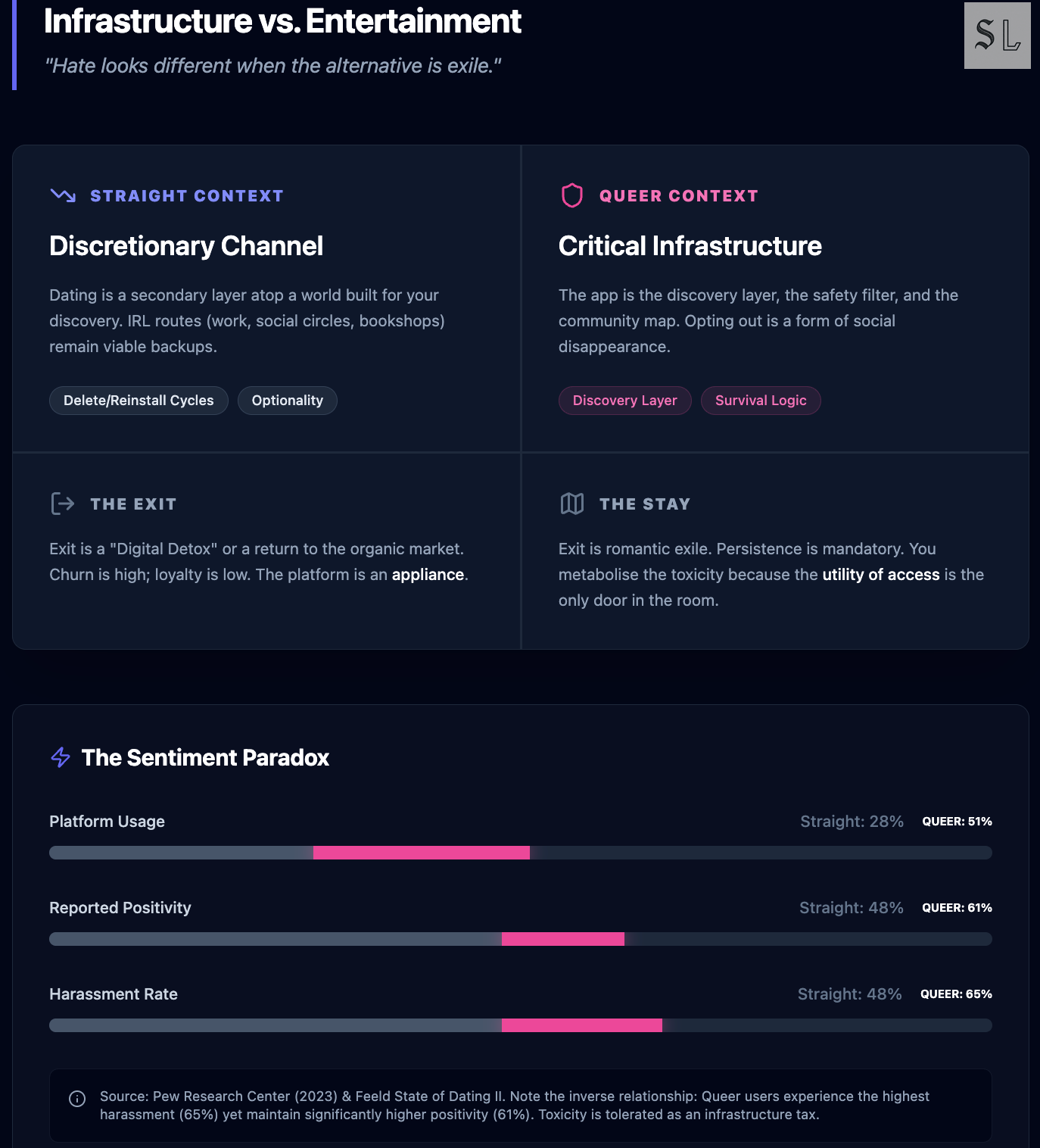

Sections 1–9 mostly describe the mainstream interface: straight dating under platform conditions. That matters because the default product assumptions (who has safe options, who can meet “organically”, who can log off without disappearing) were built around the straight world as the baseline market.

Queer dating doesn’t get that luxury. Two data points immediately illustrate the structural difference for this community:

51% of LGB adults report having used dating apps compared with 28% of straight adults.

Among partnered LGB adults, roughly 24% met their current partner online, materially higher than the general population.

For a significant share of queer people, apps are a map. That reliance changes what “hate” means.

Straight users can complain, delete, reinstall, laugh about it at brunch, then hope for a bookshop meet-cute. Many queer users delete and instantly feel a different kind of silence: not “no matches”, but “no map”. The app functions as discovery infrastructure in a world where queer visibility still isn’t evenly distributed, and where approaching the wrong stranger can carry real social or physical risk. For many gay men in smaller cities, apps can be the only viable way to meet other gay men outside limited venues or networks.

This is why the research produces a seemingly contradictory result. LGB users report higher overall positivity (about 61% positive experiences) while also facing higher harassment exposure (about 65% reporting at least one harassing behaviour). This is the double bind in numbers: more benefit, more harm. Access goes up. So does the cost of access.

The costs are hyper-sexualisation, objectification, and the specific status hierarchies that form when you run a small community through a high-frequency attention machine. Research points to widely reported phenomena in gay male spaces (sexual racism and “femme-phobia”) that are hard to quantify cleanly but recur enough in community accounts to be part of the lived ecosystem.

It can also be the safety calculus of “outness”: anonymity and privacy controls are protective for people not fully out, yet those same properties are also what let bad behaviour scale. Verification and safety measures can become double-edged in LGBTQ contexts, because tighter identity checks can increase outing risk even as they reduce fakes.

Queer dating isn’t one market and more like a cluster of overlapping micro-markets with different incentives and different pain points:

Gay men (especially in dense cities) often experience the apps as a hyper-efficient pipeline for attention and sex, and a brutal theatre for body status. Pew data in the brief shows gay/bisexual men report higher usage than lesbian/bisexual women (57% vs 46% ever used). Intention is also more mixed than the stereotype: smaller surveys cited in the brief find sizeable shares looking for relationships as well as sex, and users complain about flakiness and avoidance, not just promiscuity. The core point is structural: when the community is smaller and more legible, the app becomes both a hookup layer and a social layer, which means the same optimisation pressures hit harder and feel more personal.

Lesbian and bi women face a different constraint: the pool is often smaller, repetition is common (“seeing the same profiles”), and there’s the chronic irritation of boundary violations: men posing as women, couples “unicorn hunting”, and the general sense that products are under-built for women compared with the investment poured into gay male demand. This is still swiping commons, just with less pasture to begin with.

Trans and non-binary users carry the highest safety burden and the least clean data. Research consistently indicates major survey gaps (small sample sizes), alongside qualitative evidence of high rates of harassment/fetishisation and the constant negotiation of when and how to disclose identity. A UK NGO survey showed over 50% of trans online daters experienced discrimination or inappropriate sexual remarks. For trans users, the app is often both shield and threat: a way to screen and disclose on one’s own terms, and a surface where cruelty can be delivered at scale.

All of this makes the queer relationship to dating apps structurally different from the straight one: less “vice” and more “utility”. That difference shows up in the business too. Grindr’s 2023 revenue grew 33% (with paying users up 19% and ARPPU up 16%). Growth despite a widely critiqued “objectification culture” is not a moral judgement on users. When a platform is the primary door, people keep walking through it even when they resent what it does to them.

Yes, the apps can work. That’s why this is hard.

They do work sometimes. That’s the trap. About 12% of US adults have found a committed relationship or marriage via an app, and for partnered LGB adults the share is materially higher. So this isn’t a simple morality tale where the technology “failed”. The technology succeeded, and the success became the justification for everything else it did along the way.

A tool can be effective and still be psychologically corrosive. Cigarettes are effective at calming people down. Fast food is effective at feeding you quickly. Infinite scroll is effective at filling empty minutes. Dating apps are effective at producing matches, messages, attention… and a steady background radiation of insecurity, fatigue, and mistrust.

The deeper problem sits underneath the product debates, the gender wars, the “delete the apps” sermons, the nostalgic longing for meet-cutes in bookshops. Dating didn’t get ruined because of these apps (that’s way too simplistic). Dating got rewired because desire became measurable.

The moment you can count being wanted, you start living in relation to the count. You don’t just wonder whether someone likes you; you wonder what your “market” is doing. You stop reading a person and start reading the room. You start treating attention as feedback on identity, and identity as something you can optimise.

Privacy was not a quaint pre-internet detail. Privacy was the protective layer that made early attraction survivable. Ambiguity gave you room to interpret a silence as timing, not judgement. A maybe could stay a maybe long enough to become something real. When you replace that with a scoreboard (likes, matches, reply gaps, exposure) you change what they believe intimacy is, not just how they meet.

Perhaps the real issue is we’ve lost private desire. When being wanted is quantified, everyone becomes a speculator in a market that was never meant to be traded. And the strangest part is that we still call it dating, even as it starts to feel like everything else the internet touched: a system that knows how to measure us, but not how to hold us.