Is social media bad for people? The answer is more complicated than we thought

TikTok Isn’t WhatsApp: Why “Screen Time” is the Wrong Object of Debate

We Have Been Arguing About The Wrong Object

For a decade, the public debate over social media has been trapped in a binary loop: either it is a “toxic wasteland” destroying a generation, or the effects are “statistically negligible”. Both sides point to data, and both sides think the other is ignoring reality.

The problem isn’t the data, but the category. Using “screen time” as a metric for mental health is like trying to diagnose an obesity crisis by measuring “food time”. The category is so broad that it contains its own opposites. It treats a deeply personal WhatsApp conversation with a grandparent as functionally identical to a three-hour, algorithmically-induced trance on TikTok.

To understand what is actually happening, we have to move past the moral panic and stop obsessing over how much time we spend online and start looking at where that time goes. There is a clear signal emerging from a massive new study that just dropped in Current Psychology. By following nearly 500 teens for 100 days, researchers have finally provided the data we need to stop arguing about "screen time" as a single, blunt object and start seeing the specific machines behind the glass.

Today We’re Talking About

The “social media debate” is too vague to be useful. “Screen time” treats every platform as the same thing, when they actually work in very different ways.

On days teens spend more time than usual, they tend to feel a bit worse overall. Not just in mood, but also in how they feel about themselves and how close they feel to friends (on average, that same day).

This isn’t just a small, unlucky group. For each of those areas, more teens show a negative pattern than a neutral or positive one on higher-use days.

Once you name the platform, the story gets clearer fast. A lot of the “the research is mixed” problem comes from lumping TikTok, YouTube, WhatsApp, etc. into one bucket.

Different loop designs create different outcomes. Endless recommended feeds tend to push comparison and keep you watching; messaging apps are built more around back-and-forth with people you actually know.

There’s a weird irony in how the study works, too. It accounts for yesterday affecting today (your mood has carry-over), and it asks teens to check their Screen Time. So you’re not just living your day, you’re also seeing yourself as a number.

The Three Sensors: A Dashboard of the Self

Most research tries to find a single “mental health score,” but the human psyche doesn’t work that way. It is more like a cockpit dashboard with multiple sensors that can move at entirely different speeds and in different directions.

The van der Wal et al. (2025) study identifies three essential “dials”:

Well-being: “How happy did you feel today?”

Self-esteem: “How satisfied with yourself did you feel today?”

Friendship Closeness: “How close with your friends did you feel today?”

As I am sure you can personally attest to in your life, these sensors are rarely in perfect alignment. This is why the “mixed evidence” in literature exists. You can spend an afternoon on a platform and experience a Tangled Trade-off: your “Friendship Closeness” dial might tick upward because you felt seen, while your “Self-esteem” dial spins downward because of a subtle, automated comparison.

When we average these dials together into a single “well-being” score, the signal cancels out. The “average teen” becomes a statistical ghost, someone whose dials moved in opposite directions, leaving the researcher with a net-zero result.

The Study: 100 Days of Intensive Tracking

This wasn’t another survey asking teens to remember how they felt last month. Memories are unreliable as they are subject to “peak-end” biases and the fog of current moods. To find the loop, you have to watch the system in motion.

The van der Wal et al. (2025) study followed 479 adolescents in the Netherlands for 100 consecutive days. Every evening, the participants completed a digital diary (a total of 44,211 data points).

Crucially, the study introduced a layer of measurement reflexivity. Before reporting their feelings, teens were instructed to consult their phone’s “Screen Time” dashboard. This changed the nature of the experience as they were being asked to observe their day via a quantified metric.

By using Dynamic Structural Equation Modelling (DSEM), the researchers could filter out “between-person” noise (e.g., whether Jane is generally happier than John) and focus purely on within-person change: “On days when Jane scrolls more than her usual average, how do her sensors react?”

The Baseline: The Downward Drift

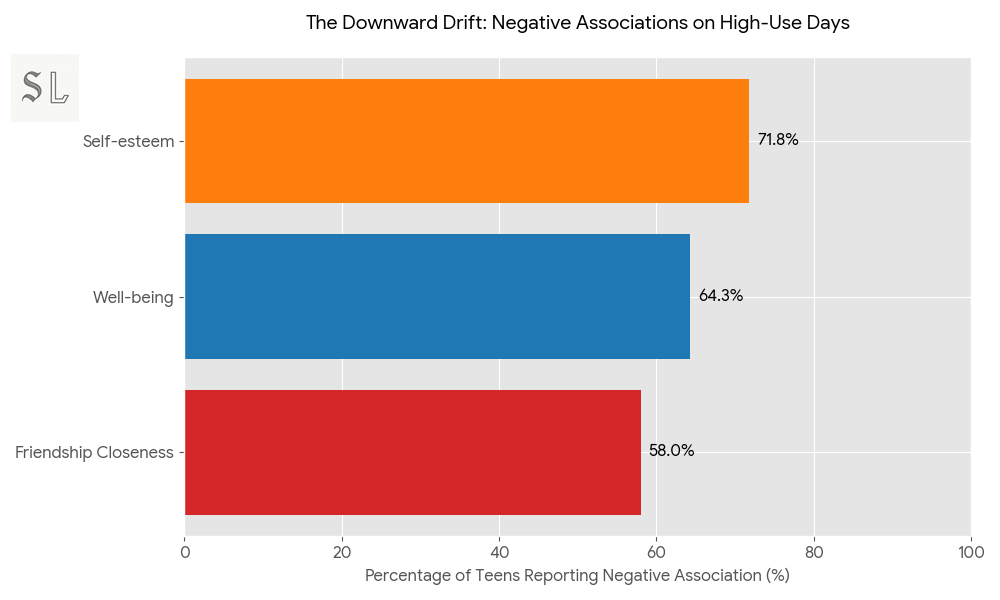

When you look at the aggregate data, a clear, sobering signal emerges. On days when teens spent more time on social media than their personal average, all three sensors (well-being, self-esteem, and friendship closeness) showed a downward association.

The “average” effect sizes might look small, but the distribution is where the story lives. This isn’t a case of a few outliers dragging down the group.

71.8% of teens felt lower self-esteem on higher-use days.

64.3% reported lower well-being.

58.0% felt less close to their friends.

For the majority of adolescents, social media use doesn’t represent a neutral hobby, and instead represents a day-to-day “dip” in their internal state. However, if we stop here, we fall back into the “social media is bad” trap. To break the stalemate, we have to look at the specific machines they are using.

The Big Reveal: Architecture as Fate

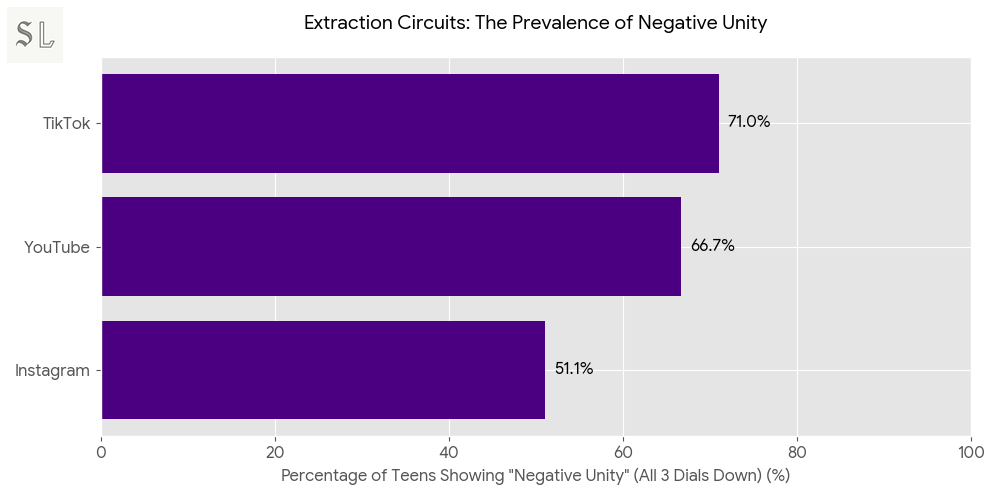

The most explosive finding of the paper is that the “mixed evidence” in the literature isn’t noise, but actually architecture. Once you stop grouping all apps together, the data splits into two entirely different worlds.

Feed Loops: The Extraction Circuits

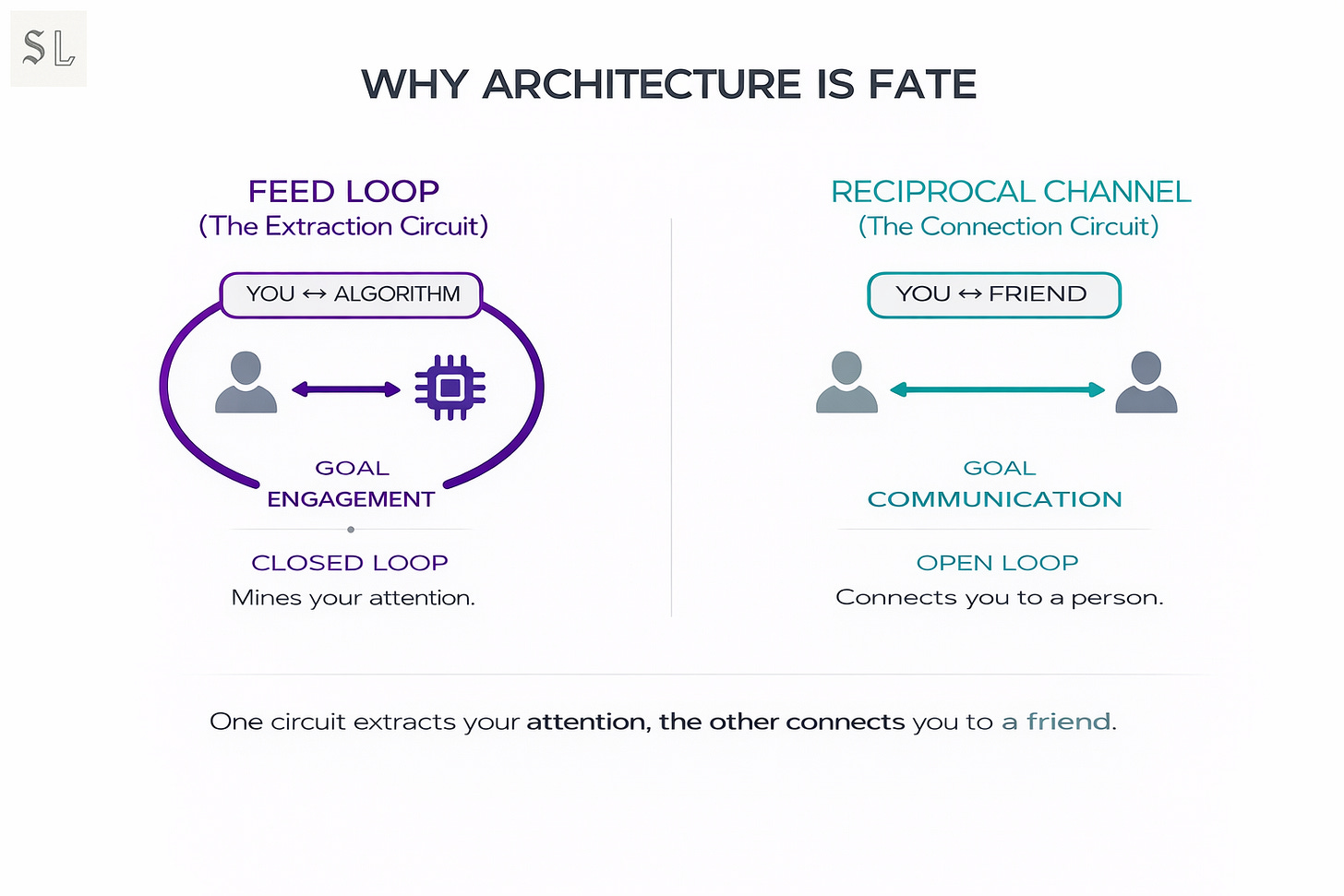

Platforms like TikTok and YouTube are “Feed Loops”. They are built on a closed circuit between a human and an algorithm. The goal of the algorithm is to keep the human in the loop.

TikTok: Approximately 71% of teens showed “Negative Unity,” meaning all three mental health sensors dropped simultaneously.

YouTube: Negative unity was found in 67% of teens.

Instagram: While slightly more mixed, it still showed negative unity for over half (51.1%) of its users.

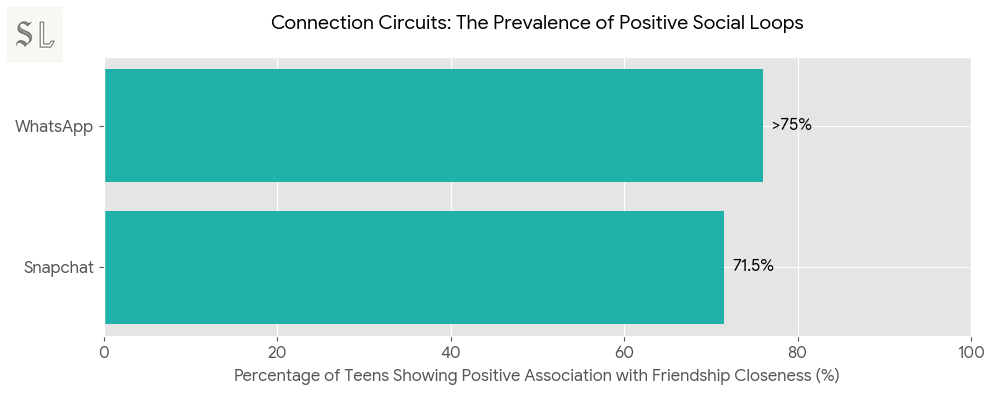

Reciprocal Channels: The Connection Circuits

Platforms like WhatsApp and Snapchat operate on a different geometry. They are “Open Loops” designed to facilitate a relationship between two humans. The app is the wire, not the destination.

Snapchat: A staggering 71.5% of teens showed a positive association with friendship closeness on days they used the app more.

WhatsApp: More than three-quarters of teens felt closer to their friends, with almost no negative impact on their self-esteem or well-being.

The architecture of the platform dictates the “fate” of the user’s sensors. On a Feed Loop, you are a data point being optimised for engagement. On a Reciprocal Channel, you are a person being connected to a peer. One circuit extracts; the other connects.

Coupled Dials vs. Tangled Trade-offs

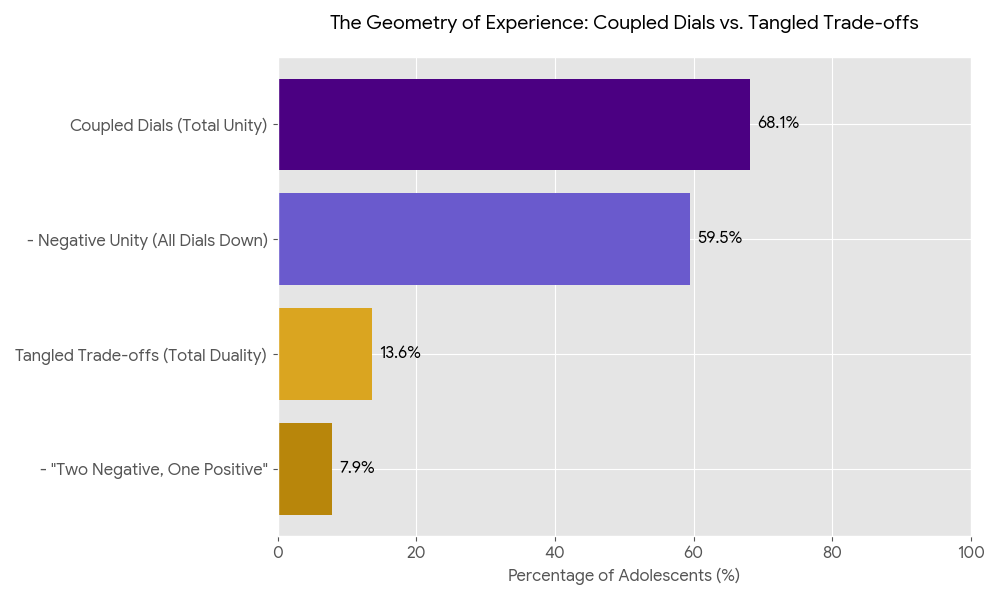

The persistent “stalemate” in the social media debate is often an averaging artefact. When researchers look at a group of 1,000 teens, they see some moving up and some moving down, and they conclude the effect is “null”. But this paper introduces a more sophisticated lens: Coupled Dials vs. Tangled Trade-offs.

Coupled Dials (Unity)

For the vast majority of adolescents (about 68.1%) their mental health sensors move in lockstep. This is “Unity”. In a Strange Loop, this represents Systemic Capture. The platform hasn’t just affected one aspect of the user, it has become the entire environment.

Of these, 59.5% are in a state of Negative Unity. When they use more social media, their well-being, self-esteem, and friendship closeness all sink together. There is no “silver lining” for this group; the loop is simply a downward slide.

Tangled Trade-offs (Duality)

Then there are the 13.6% who experience “Duality,” a system where you can move “up” in one dimension only to find you’ve moved “down” in another.

The most common duality pattern (7.9%) is “two negative, one positive”. A teen might feel significantly closer to their friends (positive) while simultaneously feeling a drop in self-esteem and general well-being (negative).

This is the “cost of doing business” in the digital age. It’s the paradox of feeling “connected” to a group that makes you feel “inferior” to its members. By recognising that some users are in a Tangled Trade-off while most are in Coupled Negative Unity, we can finally see why the literature has looked so “mixed” for so long.

Why Architecture is Fate

Why do these loops produce such vastly different results? The answer isn’t in the content of the posts, but in the geometry of the circuit.

The Feed Loop (The Extraction Circuit)

Platforms like TikTok and YouTube are built on a Closed Loop. The circuit is strictly between the User and the Algorithm.

The Goal: Engagement.

The Mechanism: The algorithm feeds you visually saturated, idealised imagery and high-arousal content to keep you watching.

The Result: This architecture triggers upward social comparison (destroying self-esteem) and “time displacement” (taking you away from real-world activities that build well-being). It is an Extraction Loop designed to mine your attention in exchange for a dopamine hit that eventually leaves the sensors depleted.

The Reciprocal Channel (The Connection Circuit)

WhatsApp and Snapchat operate on an Open Loop. The circuit is between User A and User B. The technology is merely a conductor.

The Goal: Communication.

The Mechanism: Private, reciprocal messaging with known contacts. There are no recommender systems pushing “idealised strangers” into your face.

The Result: This architecture facilitates social support and genuine intimacy. It mirrors the “Social Loops” that humans have used for millennia, just at a higher frequency.

Architecture is fate. When you step into a Feed Loop, you are stepping into a machine designed to prioritise its own growth over your well-being. When you step into a Reciprocal Channel, you are using a tool designed to prioritise your relationship with another person. The “mental health effect” is the logical outcome of the loop’s design.

The Hidden Nuggets: Memory and Inertia

The power of this study doesn’t just lie in its scale, but in its ability to see the “memory” of the system. By using an AR(1) model, the researchers accounted for Mental Inertia: the fact that how you feel today is significantly predicted by how you felt yesterday.

The system doesn’t reset every morning. Small daily associations happen within a state of momentum. While the study describes these as same-day associations rather than a proven “causal spiral,” the implication is clear: if a Feed Loop nudges your sensors downward today, you aren’t starting from a neutral baseline tomorrow. You are starting from “negative one”. The loop is a spiral that carries the weight of previous cycles.

We must also recognise that Platform Drift makes older research obsolete. The “Instagram” of 2020 (a reciprocal channel for sharing photos with friends) is not the Instagram of 2026. As the platform shifted its architecture toward “Reels” (a Feed Loop), it fundamentally changed the circuit. When the architecture shifts, the mental-health profile follows. Research that treats these platforms as static objects is studying a ghost.

Beyond Moral Panic

The debate over “social media” has been a blunt instrument for too long. We have spent years asking “Is it bad?” while the technology evolved underneath us into two entirely different species of machine.

This study gives us a way out of the stalemate. It shows us that for the majority of teens, the “Coupled Negative Unity” of Feed Loops is a real and measurable drag on their daily lives. But it also shows us that Reciprocal Channels can be a vital lifeline for friendship closeness.

The Strange Loop takeaway is that the user and the platform are not separate and instead a single feedback system. If you want to change the outcome, you don’t necessarily need to “delete social media”. You need to understand the geometry of the loop you are stepping into.

Perhaps the most important question we can take from this study is whether the architecture of an app is feeding your connection or extracting your attention. Screen time is a blunt instrument and loop architecture is the sharper one.