Sports Streaming Sucks for Sports Fans

Four Paradoxes of Modern Sports Streaming

Before we begin, do a guy a solid and take the Strange Loop Culture Survey.

Also, going to Content London or CineAsia? Me, too. Say hi.

Today We’re Talking About

Sport has never been on more platforms with more potential access. But in chasing streaming money, it has made full games harder to watch and short clips easier to scroll, trading loyal, high-value fans for cheap, replaceable views. This won’t end well.

How did this happen?

It’s a Monday night and you’re just trying to watch the game.

You know it’s on somewhere. ESPN? ESPN+? This new ESPN Unlimited thing you keep seeing ads for? Except you get an error because YouTube TV is in a carriage dispute with Disney, so all the Disney-owned channels have vanished from your line-up, including ESPN and ABC, for more than ten million subscribers.

You bounce between apps. One wants a higher tier. One says “you don’t have access to this content.” One tells you the game is exclusive to a streamer you don’t even subscribe to. After ten or fifteen minutes of log-ins, error messages and Google searches, you do what an increasing number of fans do: you give up, open TikTok, and watch the best plays as vertical video.

That’s the paradox in one night.

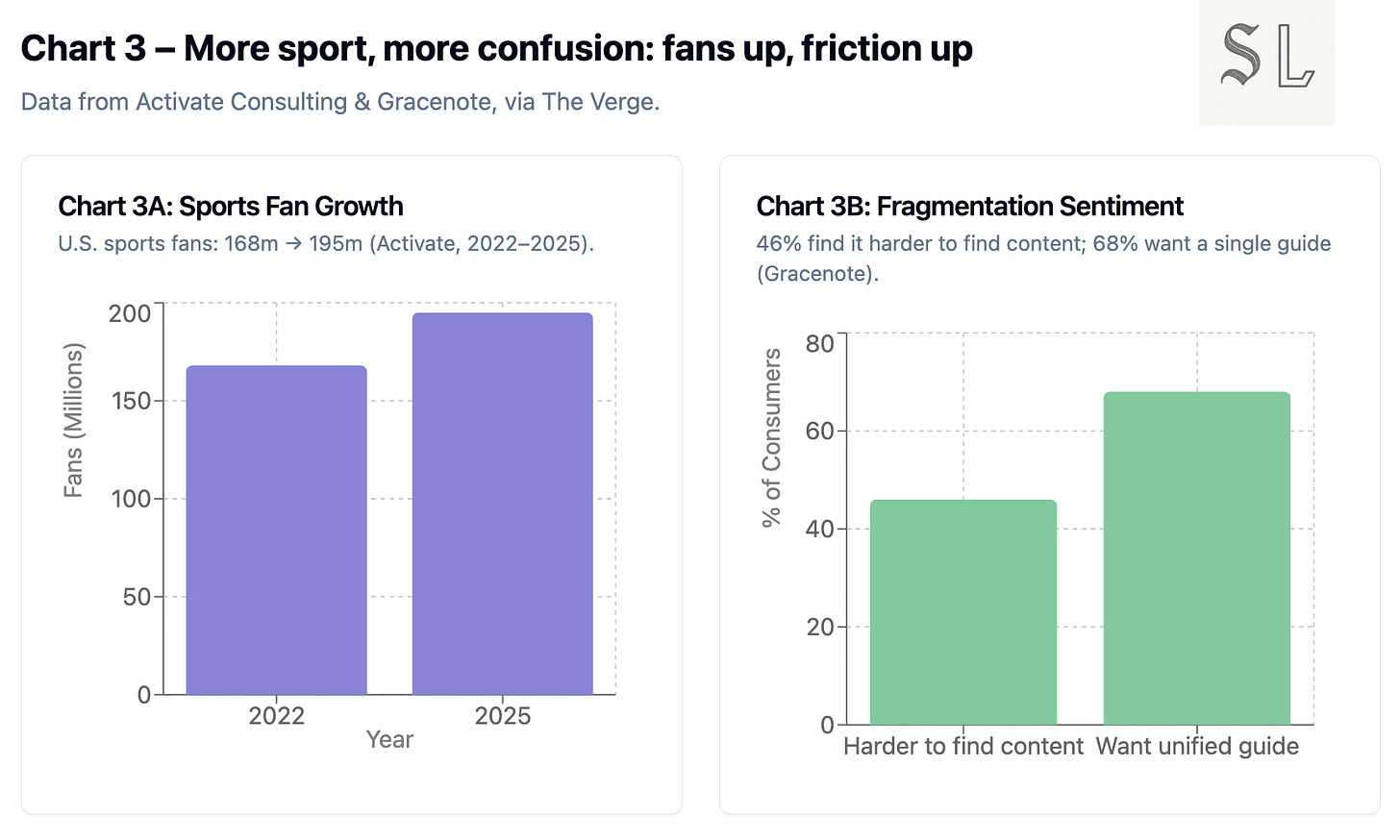

Sport has never been on more apps, in more formats, on more devices. In the 2025 NFL season alone, Amazon Prime Video, Netflix, ESPN+, Peacock and YouTube all have exclusive regular-season games, on top of linear TV and cable.

Yet for a normal fan, it has never been harder to just sit down and watch the game you actually care about. Sport is suffering from a set of structural paradoxes that tell you a lot about where the attention economy is going.

Paradox 1: More access, less game

On paper, this is the golden age of sports access.

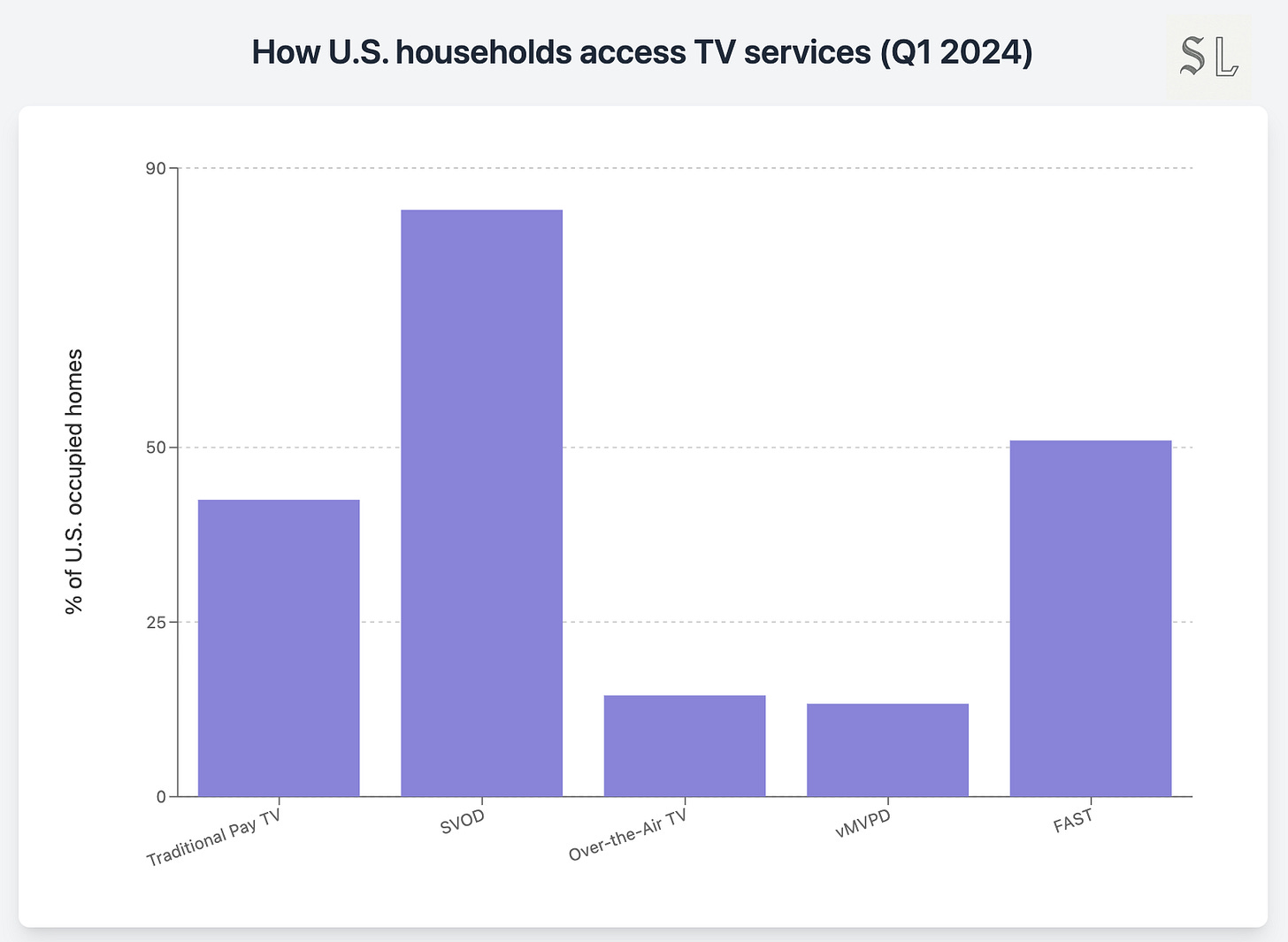

Every major league has signed streaming deals. In the US, cord-cutting has pushed live pay-TV penetration down from the mid-80s in the late 2000s to the mid-60s by 2023, and analysts expect it to fall into the mid-30s within a few years if current trends continue. The response from rights-holders has been to chase those streaming wallets hard.

At the same time, the free ad-supported TV (FAST) world has exploded. Gracenote counts around 1,850 FAST channels globally as of mid-2025, up more than 70 per cent since 2023. Sports has been one of the fastest-growing genres: sports-oriented FAST channels more than doubled between mid-2024 and February 2025, from 107 to 220 channels.

So if you look at a rights deck, sport is “more available” than ever. More games, on more platforms, across more tiers, in more countries.

From the fan’s seat, that word “available” does a lot of quiet damage.

Availability has been sliced by platform, geography, package and date. One game is global and free on Prime Video as a Black Friday stunt; another is locked inside a domestic cable bundle. Some leagues are experimenting with one-off exclusives on smaller streamers. Others are carving off packages for niche DTC apps or betting partners.

“Access” now means theoretically available somewhere, not practically watchable where you are, on what you already pay for.

Behind that experience is a specific set of mechanics:

Rights carved into ever thinner parcels: national vs local, regular season vs play-offs, streaming-only windows, one-off “event” games.

Legacy blackout rules and territorial protections imported wholesale into an on-demand world.

Bundles where buying “ESPN” doesn’t actually get you Monday Night Football unless you also buy the right streaming add-on.

Fans don’t experience any of this as innovation.

Will this match be there when I open the app? Is tonight one of the weird exclusive ones? Am I about to get another “you don’t have access” message when I’ve already paid for two different services with the right logo on them?

You can’t build love on top of uncertainty. When the ritual starts with rights archaeology, you’re already losing.

Paradox 2: The fan as sysadmin

The old cable bundle was a bad economic deal, but a great cognitive deal.

You overpaid. The channel line-up was bloated. But the contract between fan and system was clear: you pay one bill, plug in one box, and almost everything you care about is “just there”.

The streaming era flipped that trade.

The economics can be better, especially if you’re disciplined about cancelling services between seasons. But the labour of bundling has been quietly outsourced to the fan.

To be a serious follower now, you have to:

Track which league’s rights moved where this season (and which rights are in which country).

Stack vMVPDs, niche DTC apps, “free” FAST channels and ad-supported tiers.

Game free trials, promotional prices and calendar quirks just to avoid paying double.

Every year, the mental spreadsheet gets more complex: which email, which password, which card, which address, which blackout zone.

If you live in a market where regional sports networks or local blackout rules still apply, you can easily end up in the situation where the out-of-market streaming product is blacked out in your postcode, but the local channel carrying the game is missing from your skinny bundle.

Even the high-intent fans (the ones willing to pay, willing to search, willing to switch apps) arrive at kick-off with decision fatigue already built in.

When your most committed customers feel like they’re doing IT support for their own leisure time, something is structurally off.

And the system behaves exactly as you’d expect any overloaded human system to behave: under pressure, it collapses into the lowest-effort option. Not “no sport”, but highlights in the feed. Short clips. The one thing that is always there and never asks you to remember which package the Premier League is in this year.

Paradox 3: The broken commons

Live sport is one of the last rituals that reliably cuts across age, class and geography.

It’s entertainment and infrastructure for conversation. The thing you can talk about with your friend, your colleagues and the stranger next to you at the pub without negotiating context.

The old set-up reflected that. Big matches on free-to-air or basic cable. Games in pubs. Office small talk the next day built on the assumption that “we all saw that”.

Fragmentation creates confusion and attacks that commons.

Different games sit behind different paywalls. Some are exclusive to relatively niche apps. Others are available only to households with the right broadband provider, or the right streaming bundle in the right territory.

The odds that you and your friends all watched the same full game, in real time, are getting worse every season.

Zoom out and this sits inside a much bigger pattern. Everything else in culture is already personalised and out-of-sync. Social feeds are individually tuned. On-demand series are watched on your own schedule. Even news is pushed algorithmically.

Live sport should be the place where the timeline snaps back into something shared again.

Instead, rights strategies are slicing that live timeline into micro-audiences. This cohort saw it on cable. That cohort watched on a DTC app. Another group only saw the key moments as TikToks fed to them by whatever the recommendation system thought would drive engagement.

The more sport becomes “something you might catch on whatever bundle you currently have”, the less it functions as a civic ritual and the more it becomes just another content vertical in the feed.

At that point, when you ask why younger fans feel less attached to clubs, leagues and national teams, the answer is pretty straightforward: they’re not sharing a world, they’re sharing an algorithm.

Paradox 4: Clips up, loyalty down

It all looks like progress, until you follow the money.

The system is making full games harder to watch and short clips easier to scroll. In the short term, that grows reach. In the long term, it cannibalises the behaviour that justifies billion-dollar rights deals.

Look at how younger fans are actually behaving:

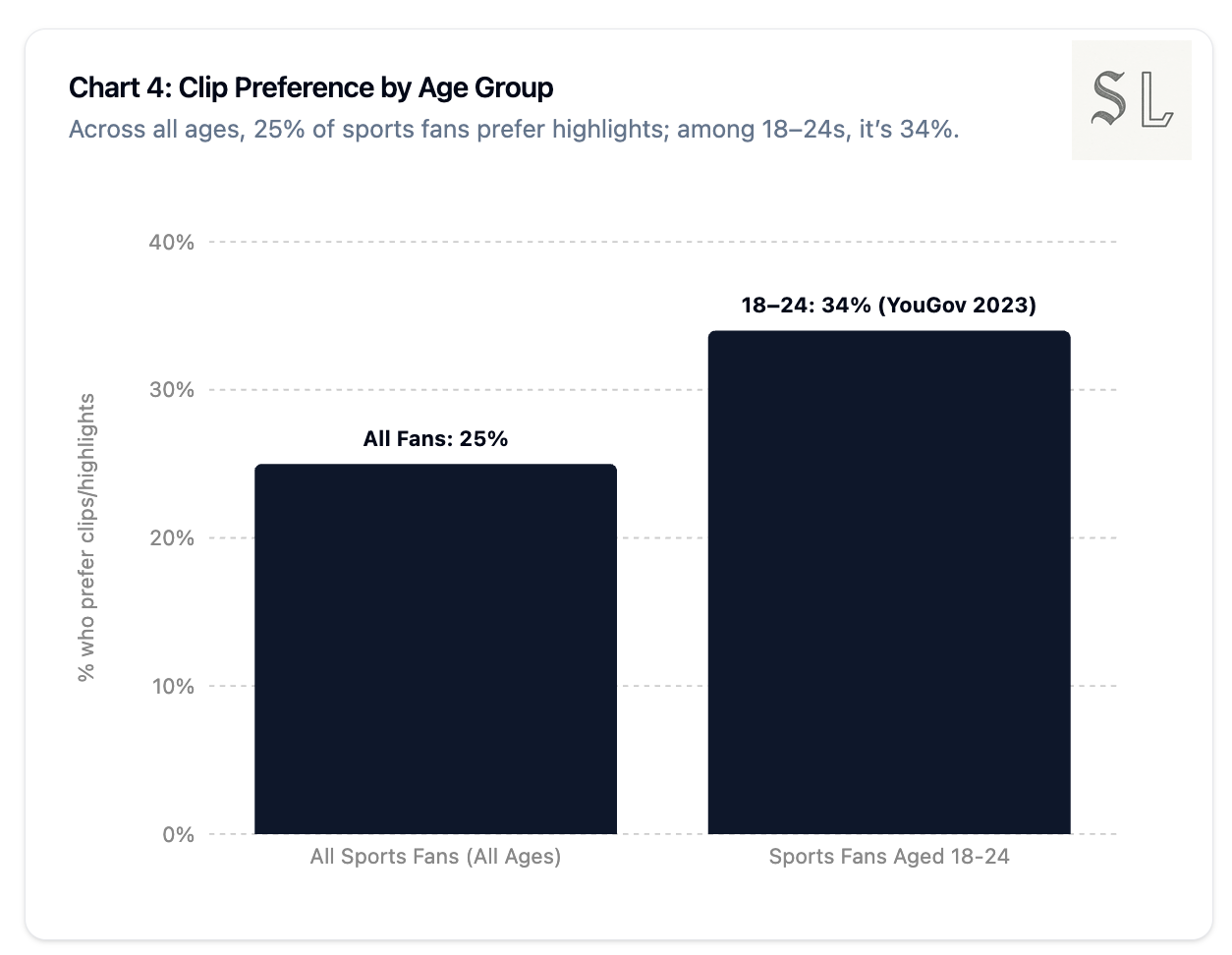

A YouGov study found that around a third of engaged global sports fans aged 18–24 already prefer watching clips or highlights to full matches. Earlier research in the US put it more starkly: roughly half of NFL and NBA fans aged 18–34 said they preferred highlights over full games.

Sports executives can see the same thing. In Altman Solon’s global sports survey, two-thirds of senior executives said they were concerned about the relevance of live games as younger fans gravitate towards highlights, documentaries and short-form video.

The behavioural shift is simple:

The full-game fan gives you two or three hours, rides the complete emotional arc, and develops deep identification with a team or athlete.

The highlight-native fan gives you five to ten minutes of vertical video: goals, dunks, fights, memes – surfaced by whatever the algorithm thinks will perform in that moment.

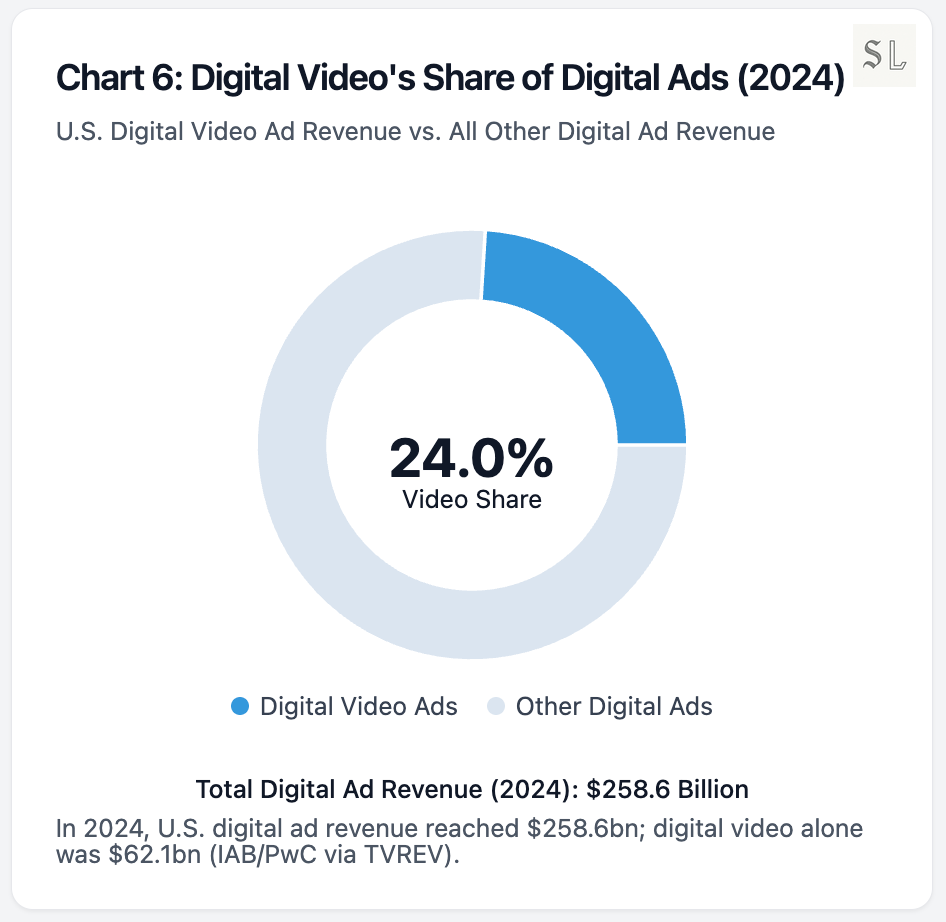

From a pure eyeballs perspective, clips look fantastic. Digital video is the fastest-growing segment of internet advertising, with revenues up more than 19 per cent year-on-year to over $60 billion in 2024. Short sports clips are a natural part of that growth.

But not all minutes are equal.

A full game is high-ARPU attention. Premium ad slots. Jersey patches. In-game sponsorship. Betting integrations. Tickets and hospitality. Travel. Food and drink. Direct-to-consumer subscriptions and CRM data tied to a known household.

A clip is low-ARPU attention. The ad revenue is primarily captured by the platform; leagues get a revenue share and some branding.

You can see the difference in the media economics. A connected-TV sports spot might command a CPM north of $30–40 in many markets, while generic digital video impressions on platforms like YouTube can sit materially lower. The exact numbers vary, but the hierarchy is stable: full-screen, lean-back, live sport is premium; skippable, scrollable video is not.

Over a decade, shifting behaviour from “game time” to “clip time” becomes a slow leak in pricing power and brand depth.

And there’s a second shift underneath that: who actually owns the relationship.

If your default habit is “I open TikTok to see what’s happening in sport”, the platform owns you. The league is just one supplier in an endless scroll of content.

Algorithms decide which league gets surfaced, which team gets favoured, which athlete becomes a meme. Leagues and broadcasters have much weaker data on who these viewers are, what they care about, and how to move them up the value ladder into attendance, merchandise or paid subscriptions.

Clips also flatten hierarchy. Everything becomes “the coolest thing that happened last night”, whether it was the Champions League final or a friendly with a funny own goal. It’s much easier to switch allegiance when your relationship is with the daily highlight reel, not the grind of a season.

Put simply: the industry has optimised the teaser and turned the core product into a puzzle. In the long run, that’s a bad trade.

So what? The quiet long-term risk

For leagues and rights-holders, this isn’t just an irritation, but a very real strategy problem.

You cannot keep inflating rights fees on the story that live sport is the last must-watch linear television, while simultaneously making the live product feel like admin.

If full-game viewing erodes, so does the story you tell sponsors and broadcasters about “unmatched live reach”. The more your audience experiences you as clip fodder on social platforms, the harder it is to argue that your fixture list deserves a premium over every other attention sink.

Over time, your IP risks becoming meme fuel first, premium product second. For streamers and platforms, there is an opportunity hiding in this mess.

Most services are competing on catalogue size, original series and headline rights. Very few are competing on legibility. On being the place where a normal human can say, “I want to watch my team,” and actually get a straight answer.

There is a clear open lane for whoever is brave enough to simplify: honest, legible sports tiers, sane packaging, clear communication on what is where, search and discovery that speak in fixtures and teams, not channel logos and product names.

Whoever feels like “the home of seeing the thing, not worrying about the thing” will have a durable advantage.

For fans, the choice is not really between more options and fewer options.

It’s between:

A labyrinth where you slowly retreat into clips because every attempt to watch a full match feels like a test of patience.

A system where someone takes the job of rebundling seriously again, even if that means admitting that the pure unbundling phase has gone too far.

Sport as a warning label

Sports streaming is just the cleanest case study of a broader pattern: We take a simple shared ritual. We financialise and unbundle it. Then we ask individuals to do the recombination work themselves.

You can see the same pattern in news, television, music, even education. More theoretical choice. Worse felt experience. A slow drift into shallow, platform-native consumption because that is the only thing that still “just works” when everything else is a maze of log-ins and exclusions.

The difference with sport is that people notice faster. When the people who love the game most find it this hard to watch, the system is not just annoying.

It’s telling you something about where the whole attention economy is headed.

Notes & further reading

If you want to go deeper than one annoyed Monday night, here are the main things under the hood of this piece and where to find them.