Top 10 Predictions for 2026 (Part 1)

Year 9 of predictions. Yes, I will be quoting myself back at myself in 12 months.

I’ve done annual predictions for eight years now and by year’s end (each year) I’ve gotten 10/10. That’s either a skill, a sickness, or proof reality has become embarrassingly predictable. But how? you might ask. It’s not really that hard.

Everyone asks: “What’s coming next?”

Wrong question. That’s sequel-thinking: the belief the world releases updates like a prestige drama. Season 2. Season 3. A tasteful spin-off. A merch drop. Everyone claps.

Good predictions are really just systems-thinking. Systems are all based on the same three things:

feedback loops

lock-ins and

incentives

The four rules I use (so you don’t have to raw-dog the future)

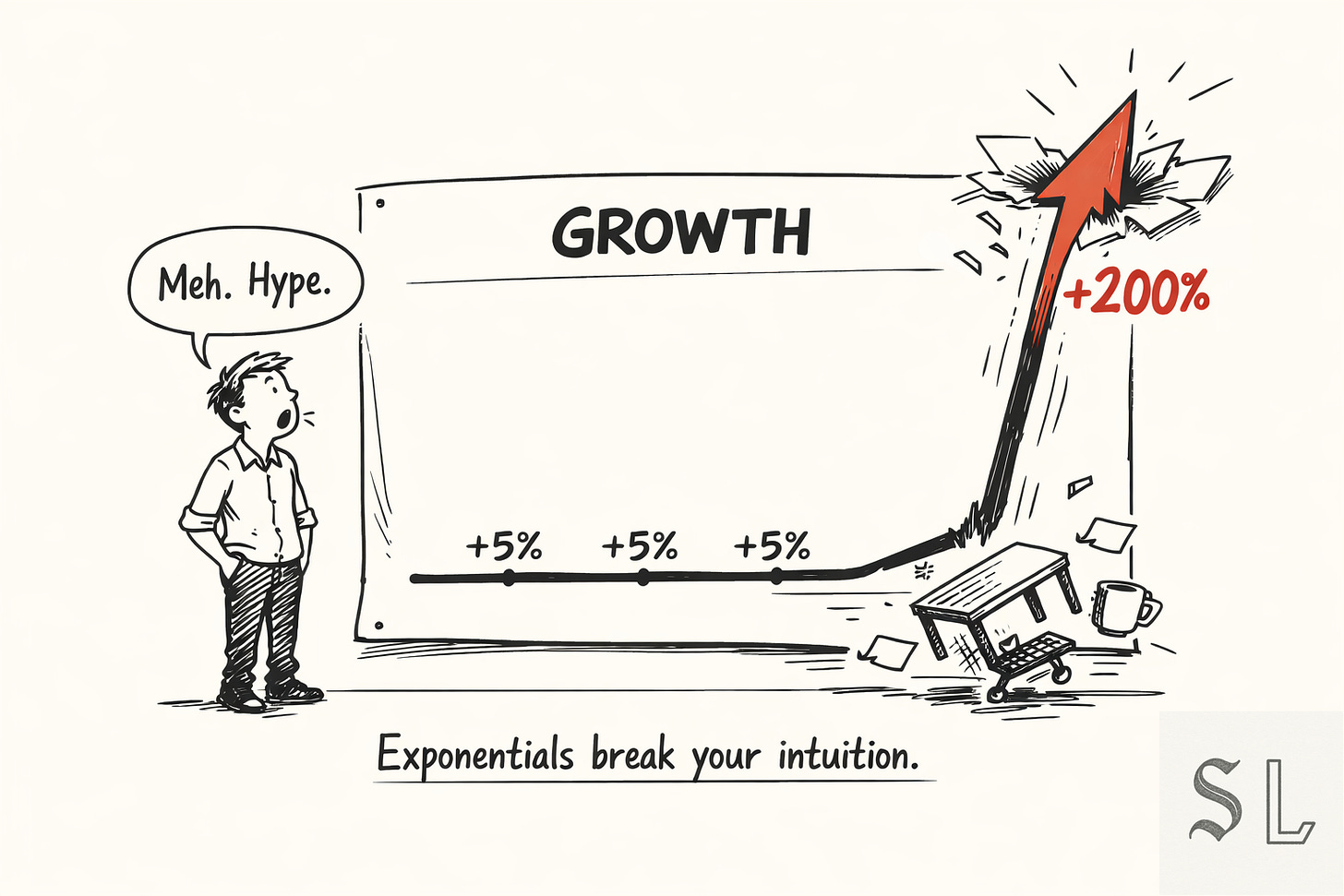

1. Exponentials break your intuition

Most change is compounding, not actually linear.

What your brain expects: steady progress. +5%, +5%, +5%.

What happens instead: +5%, +5%, +5%… then suddenly +200%, because compounding crosses a threshold.

Why it fools people: the early phase looks like “hype” or “not that big a deal”, because the curve is flat at the start. The shock arrives when the curve goes vertical.

Translation: by the time something looks urgent, it’s usually late. The winners spot the rate of change, not the headlines.

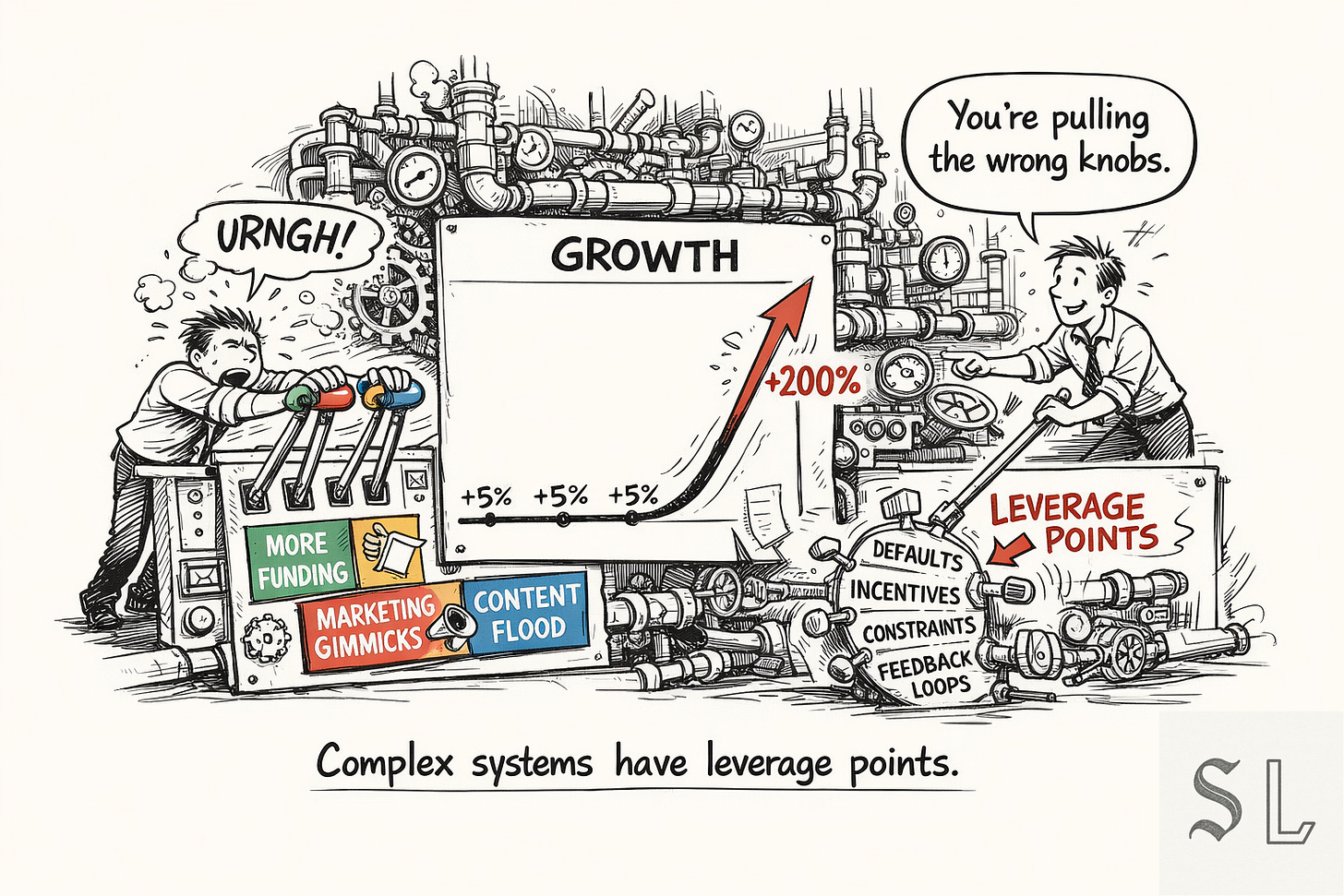

2. Complex systems have leverage points

In systems with lots of moving parts, not all knobs matter equally.

A system has stocks (things that build up: users, trust, debt, attention) and flows (what changes them: churn, referrals, interest rates, recommendations).

Most people push on obvious levers (more marketing, more content, more features) because they’re visible and feel “active”.

But the system is usually controlled by a few high-leverage points:

defaults (what happens if you do nothing)

incentives (what gets rewarded)

constraints (what’s permitted)

feedback loops (what reinforces itself)

Translation: “strategy” is often just activity. Real strategy is finding the small lever that moves the whole machine.

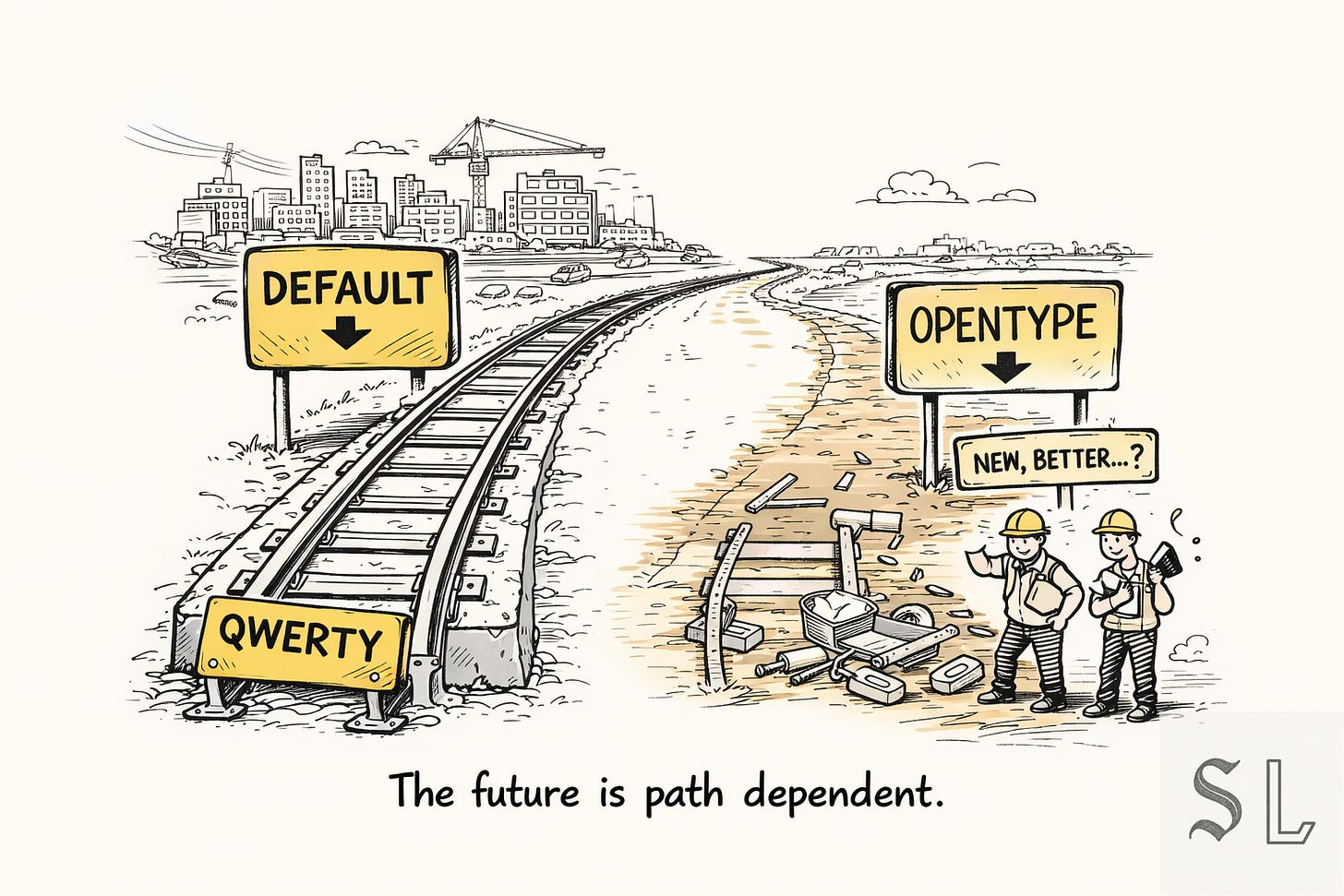

3. The future is path dependent

Early choices harden into infrastructure.

Once a behaviour becomes a default, everything gets built around it: tools, habits, contracts, integrations, politics.

Even if a better option exists later, switching costs become enormous because you’re not replacing a feature, you’re replacing a rail system.

QWERTY is the classic example: not the “best” keyboard layout, just the one we’re all stuck with because the whole world trained on it.

Translation: the most important moments are when new defaults are still fluid. After that, you’re negotiating with concrete.

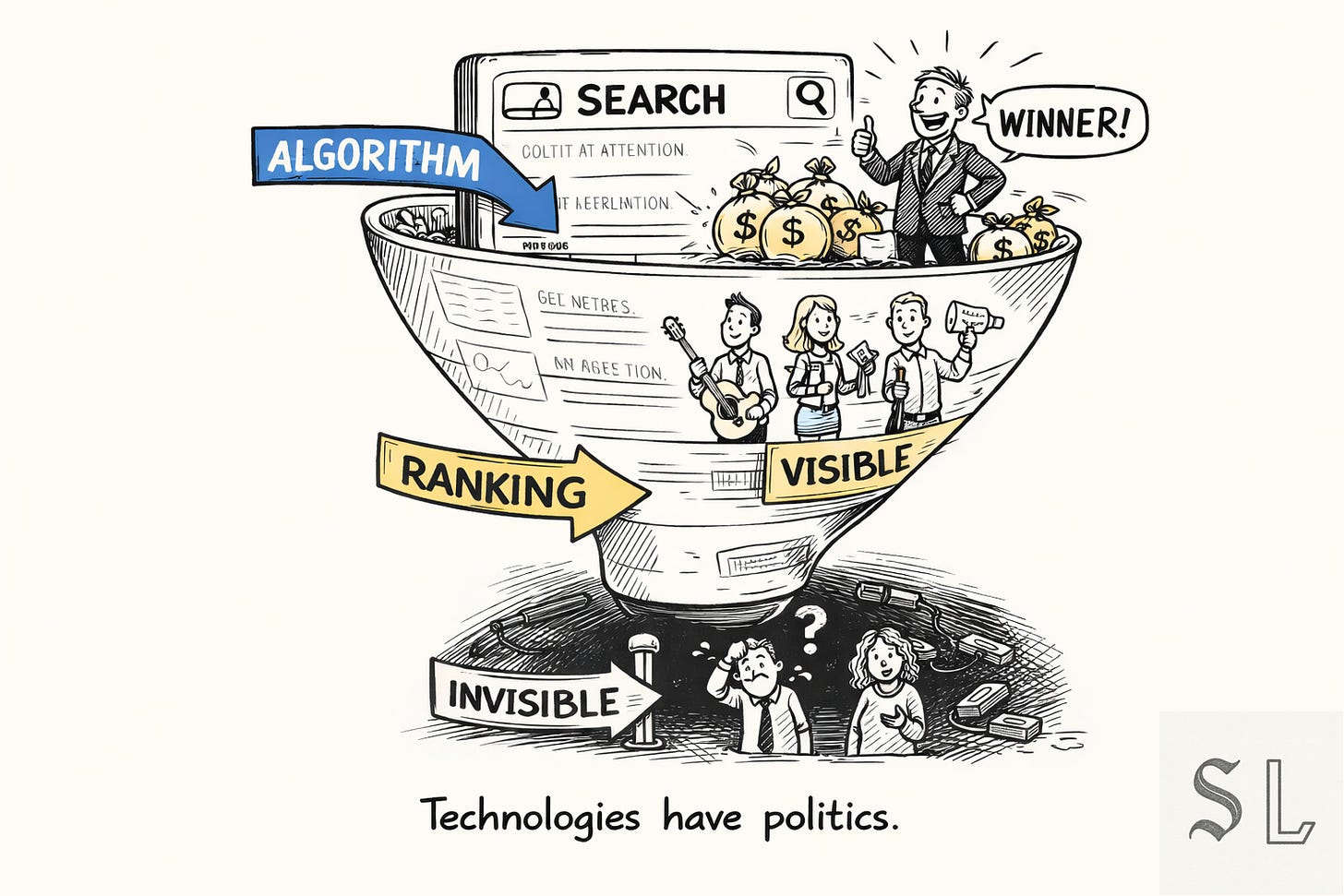

4. Technologies have politics

Tools don’t just enable behaviour, they choose winners.

Any system that ranks, recommends, or filters is making value judgements:

what counts as “good”

what gets distribution

what gets suppressed

And because attention and distribution convert into money, ranking becomes income.

That’s why “every ranking system is a wage system”: it determines who gets visibility (and therefore jobs, deals, bookings, promotion) and who gets pushed into the invisible middle.

Translation: algorithms aren’t neutral. They’re economic policy, enforced silently, at scale.

So: Watch the curve, find the lever, protect the default, and treat rankings like power. With that, part 1 of the ten 2026 fault lines (= predictions).

1. Big AI: From word models to world models

What it is

AI stops being a chat box and becomes infrastructure.

The interface still looks like a polite little text window, but that’s just the steering wheel. Under the bonnet it’s turning into:

model + tools + memory + planner + execution loop + logs

So it goes from:

“help me write an email” to

“run the whole workflow, coordinate the tools, ship the output, document what happened, and only wake me up if the building is on fire.”

The technical shift is boring-sounding but massive: state.

Word-model behaviour is great at producing plausible language.

World-model capability is about keeping track of what is happening over time (across text, images, video, apps, files, tasks), so the system can plan and act without resetting to goldfish mode every five minutes.

A simple way to think about it: an agent can do things; a world-ish model can keep its place while doing them.

Why I think it

Because the bottleneck has shifted from “can it answer?” to “can it stay on task long enough to finish?”

Long-horizon autonomy is already being publicly claimed with numbers. Anthropic told Reuters that a customer had Claude Opus 4 coding autonomously for nearly 7 hours, and an Anthropic researcher set it up to play Pokémon for 24 hours; the prior model was reportedly around 45 minutes of gameplay.

The maths of reliability forces a new architecture. Even if an agent were 99.9% reliable per step (which is generous in the wild), the probability of a clean run over 1,000 dependent steps is ~0.999¹⁰⁰⁰ ≈ 36.8%. Over 10,000 steps it’s effectively zero (~0.0045%).

We now have “proof-of-possibility” research in the open. MAKER reports completing a task with over 1,000,000 LLM steps with zero errors via extreme decomposition into microagents plus error correction/voting. This is the important bit: it’s not “the model got perfect”; it’s “the system made failure expensive”.

The web is being re-optimised for machines, not humans. When only 360–374 clicks per 1,000 Google searches go to the open web, you’re watching “browse” get replaced by “answer”.

Scale is becoming machine-scale. Google said it went from 9.7T to 480T monthly tokens processed across products/APIs year-on-year, then later said it had doubled again to 980T monthly tokens. That’s a world where machines are no longer guests on the network but the majority traffic constituency.

What it will mean

This is the bit people keep missing because they’re distracted by whether the bot can write a haiku.

“Set and supervise” becomes the core skill. You don’t prompt all day; you brief an agent, constrain it, let it run, and review output like you would a junior. The new literacy isn’t “prompting”, it’s:

scoping (what counts as done)

constraints (what it must not touch)

verification (how it proves it’s right)

escalation (when it wakes you up)

World models become virtual backlots. Studios and game teams will use simulated environments to test:

worlds and rulesets (does it hold together?)

characters and dialogue (does it stay consistent?)

player/fan behaviour (what breaks? what sticks?) before they burn real money on production. Pre-vis becomes pre-everything.

In short: 2026 is when the agent stops being your clever friend and becomes your co-worker. And like all co-workers, it needs boundaries, audits, and someone responsible when it decides to be creative with the database.

2. Peak Social is behind us: the rise of new attention measurement

What it is

Social media isn’t dying because we all got more spiritual but because the main feeds got worse.

The “big public square” idea was: you show up, you see your people, you talk, you find culture. What we got was: an ad machine wearing the skin of a town hall.

Your friends stopped being the main event.

The feed got flooded with content that’s optimised for reaction, not connection.

The experience became repetitive, hostile, and weirdly exhausting, like living inside a shopping centre where everyone is yelling.

So people didn’t stop wanting entertainment or community, they just stopped wanting it there.

What replaces it isn’t “less attention”. It’s attention moving house:

Sparks: quick hits that travel fast (clips, memes, snippets). You dip in, you laugh, you scroll, you leave.

Depth: places you actually sink time (streaming, gaming, UGC worlds). Not social, but absorbing.

Peak intensity: where you feel human again (live events, group chats, private communities, high-trust rooms).

Which means the feed becomes what it’s best suited for now: a billboard and a battleground. And the real relationship (the actual conversation, the “are you coming?”, the “what do you really think?”, the “help me decide”) moves indoors, into places that aren’t designed to monetise your nervous system.

Why I think it

Time spent on social peaked in 2022 and has declined since (GWI analysis for the FT). In the developed world, adults averaged ~2h20/day at end-2024, nearly 10% down vs 2022, with the biggest declines among young people.

Meta’s own numbers show the ‘friends’ layer shrinking hard. In 2025, only 17% of time on Facebook was with friends’ posts (down from 22% in 2023); on Instagram, 7% (down from 11%). Zuckerberg framed Facebook as “discovery and entertainment” now, which is corporate for “we’re basically TikTok with history”.

Once platforms optimise for velocity + ads, the user experience degrades into content supply chain, not human life. The visible internet then gets disproportionately shaped by:

hyper-active minorities (fan armies, clippers, operators)

coordinated behaviour (rage cycles, pile-ons, brigades)

everyone else watching silently, then talking elsewhere

What it will mean

A view is cheap now. It can be bought, botted, clipped, or accidentally autoplayed. It doesn’t tell you whether anything landed. The only metrics that matter are the ones that prove a thing has crossed the line from “content” into “culture”.

So the KPI becomes vitality: is this thing alive in other people’s minds when you’re not paying to force it there?

You’ll start judging success by signals that are harder to fake and more correlated with real demand:

Repeat behaviour: people come back unprompted (rewatches, replays, re-listens).

Transformation: the audience changes the thing (memes, edits, stitches, fan art, theories).

Coordination: people organise around it (group watches, watch parties, “you have to start this tonight” texts).

Intent: people seek it out (search spikes, saves, playlists, wishlists).

Migration: it pulls people off the public feed into rooms you can’t buy with CPMs (Discord joins, WhatsApp forwarding, live attendance, paid membership).

That’s the difference between “we got reach” and “we got a movement”.

Two consequences:

Public reach becomes the trailer. The real business is what happens after: whether the spark turns into depth, and depth turns into a room.

Corporate language shifts because corporate reality shifts. Earnings calls start talking less about vanity engagement and more about retention, repeat, community pull-through, and paid conversion, because that’s what survives once the feed stops being a reliable distribution engine.

And then the real curveball: Personal AI becomes the new ratings box. When people have agents choosing what to watch, read, buy, and book, the question changes from “did we trend?” to something far more brutal:

Did the agent recommend us?

Did we get queued?

Did we get booked?

Did we become the default?

Because in a world of infinite content, the scarce resource isn’t attention but intentional selection.