Why Modern Life Feels Boring and Catastrophic at the Same Time

Notes from Square Thirty-One

👋🏼 2025 took me across three continents and more than fifteen stages. One parable repeatedly stuck with audiences more than anything else. As we start to wind down the year and reflect on what’s ahead, it made sense to revisit and build from that parable.

The Linear Organism

There is a menacing flaw in the human nervous system: we are incapable of feeling the difference between a slope and a wall.

To understand why modern life feels simultaneously boring and catastrophic, we must revisit the chessboard. You know the fable: an inventor presents a game to an Emperor. The Emperor, pleased, offers a reward. The inventor asks for something simple: one grain of rice on the first square, then double it on every square after that. The Emperor, a linear thinker, laughs. He sees a modest pile. He imagines a sack of rice. He grants the wish.

1, 2, 4, 8, 16.

The trick is that doubling doesn’t feel like much until it does. Every ten squares is roughly a thousand-fold jump. So the 10th square is 512 grains. The 20th is 524,288. The 30th is 536,870,912.

The Emperor does not realise what he has agreed to. By the end of Square Thirty-One, the square itself holds 1,073,741,824 grains; the running total owed is 2,147,483,647. By the end of the board, it is 18,446,744,073,709,551,615 (about 18.4 quintillion, or said another way, 18.4 billion billion). He thinks he is approving a silly reward. He is signing an obligation no empire can physically pay. He has committed to more rice than exists on the entire planet.

But the ruin does not happen at the end. It happens at Square Thirty-One.

Square Thirty-One is where the maths breaks intuition. The running total has crossed two billion, which is where the curve stops feeling like growth and more like a wall. The curve has gone vertical. But to the human eye, looking from our day-to-day position, the pile on the board still looks merely “large.” It does not yet look fatal.

This is the “Still Fine” zone of life. It is the zone where the system has gone exponential, but the user is still calibrating for a linear world.

We are currently living on Square Thirty-One.

The inputs we process daily are operating on a vertical curve that has long since outrun our ability to map it. We still speak of “keeping up” with the news or “learning” a new skill as if we are walking a path, but the path has become a lift-shaft.

Consider the velocity of knowledge. Until the early 20th century, Buckminster Fuller estimated human knowledge doubled on roughly a century cadence. By 1945, that estimate had collapsed to around twenty-five years. After that, the curve becomes harder to state cleanly, because “knowledge” isn’t a measurable stock. Knowledge is a story we tell about information. But the substrate beneath it is measurable, and it has gone vertical: IDC projected the global datasphere growing from ~33 zettabytes in 2018 to ~175 zettabytes by 2025. Whatever number you prefer for “knowledge doubling,” we are approaching a horizon where the substrate of what we know doubles every twelve hours. The lived result is that we are not “busy,” but mathematically incapable of being “informed” in a system where the half-life of a fact is shorter than a sleep cycle.

The “AI Effect” is the ultimate anaesthetic for this vertigo. We watch the training compute of notable AI systems double roughly every six months, a pace that makes the old speed of the digital age look like a standstill. Yet, we perform a psychological sleight of hand: the moment a machine performs a miracle, we stop calling it “intelligence” and start calling it a “tool”. We rename the vertical wall a “feature” so we don’t have to admit we are no longer the fastest thinkers on the board.

Even the planet has abandoned the slope. We treat climate change as a linear progression of heat, yet the reality is a series of reinforcing feedback loops. When melting ice reveals dark water, the ocean absorbs more heat, which in turn melts more ice. These are not “trends”. They are tipping points: the moments a system becomes self-sustaining and independent of our input.

We are bored when we should be experiencing vertigo.

The cognitive dissonance of the modern age is not that things are moving too fast, as logical as that might sound. The issue is that our nervous systems evolved in a linear environment, where an additional unit of effort produced a proportional result. We are biologically coded to interpret the world as a gentle slope, so we normalise the doubling. We treat the first viral shock as an anomaly, the second as a trend, and the third as background noise. We are judging the speed of a rocket with a speedometer built for a horse.

The “Still Fine” feeling is a lagging indicator of a crash that has already happened, not a sign of safety.

The Infinite Good Enough

In the original fable, the Emperor’s problem is scarcity. He goes bankrupt because he runs out of rice. He cannot physically fulfil the obligation of the board. Our problem is the inverse: we are not running out of rice, we are suffocating in it.

The “rice” on our board is no longer grain, but cognitive output. It is the slurry of code, copy, strategy decks, emails, and media that constitutes the modern knowledge economy. For the last thirty years, the cost of producing this material was high enough to act as a natural dam. It took time to write a bad email. It took money to shoot a mediocre film. Friction was the filter.

But on Square Thirty-One, as training compute doubles every six months, the cost of producing plausible output collapses. We enter the era of zero marginal competence.

The problem is not that the machine produces rubbish. We can ignore rubbish. The problem is that it produces competent approximations at industrial scale: emails and decks, yes, but also DMs, news summaries, “helpful” threads, autogenerated plans, and the relationship text you feel you owe. This is the age of the Infinite Good Enough: billions of units of B-minus output that mimic substance just well enough to trigger your responsibility reflex. Each unit is cheap to generate but expensive to evaluate. The result is a permanent “review tax” on your attention, a death by a thousand competent drafts.

Enter “The Treasurer.”

The Treasurer isn’t just your work self. It’s the part of you that feels morally behind on everything: messages, news, admin, friendships, health, culture, even rest. They are the conscientious executive function that wakes up at 5:00 AM to “get ahead of the emails.” The Treasurer is diligent, responsible, and doomed.

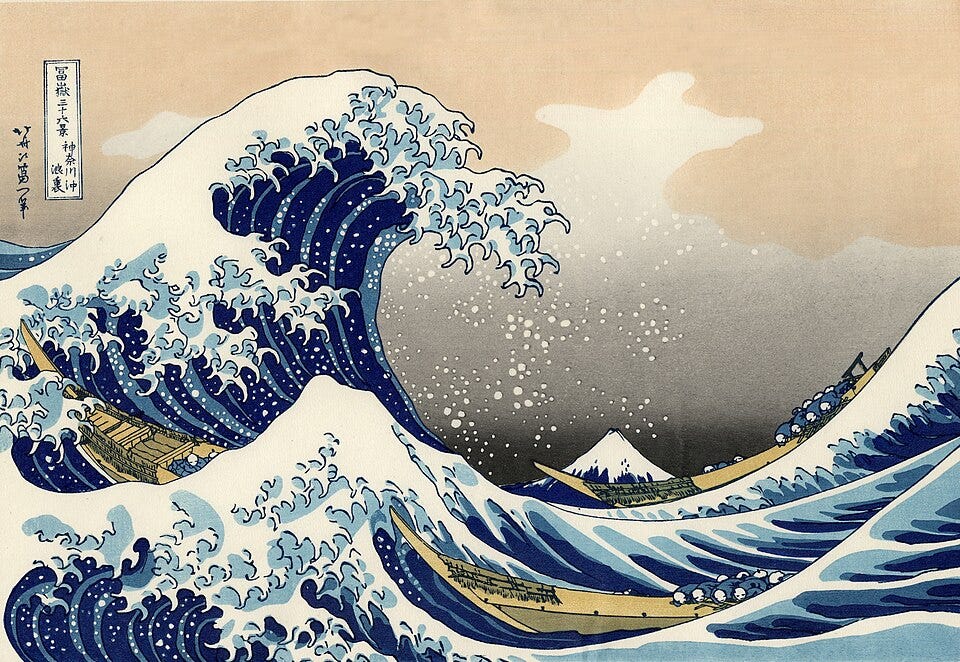

They are operating on a linear model of labour. They believe that if they just read faster and organise better, they can clear the board. They are budgeting for Square Seven, where the inputs are manageable integers. But the board is flooding. When the cost of generating “passable” work drops to zero, the volume of obligations goes vertical. The Treasurer is trying to audit a tsunami with a pocket calculator.

The Treasurer fails not because they are lazy, but because they are trying to pay for an exponential debt with linear currency. They do not see that the harder they strive, the farther they get from the centre. Because there is a constant goal, that striving creates a permanent interruption to presence. They are trying to be “responsive” in a world that has structurally guaranteed their negligence.

The Illusion of Linear Agency

Why does the Treasurer persist? Why do we continue to answer the emails, track the news, and optimise the calendar long after the math has proven these acts futile?

Because the Treasurer suffers from the illusion of linear agency. This is the obsolete belief that comprehension is a precursor to control.

The Treasurer operates on the assumption that if they can just understand the complexity (if they can read enough newsletters, listen to enough podcasts, and parse the geopolitical shifts) they can find their safe harbour within it. They believe that with enough data, the chaos of Square Thirty-One can be tamed into a strategy.

This is a category error. On an exponential board, you are not the player moving the piece. You are the square the piece lands on.

The systems we now inhabit, algorithmic markets, climate feedback loops, generative intelligence, are not just “complex”. They are operationally unintelligible to the individual mind. They do not offer linear cause-and-effect narratives. They offer verticality.

To acknowledge this is to invite a specific kind of vertigo. It is the realisation that your diligence is no longer legible to the system you are trying to manage. You can be responsible, informed, and highly competent, and still be structurally late. To survive this, we edit the tape. We smooth the exponential into something our linear minds can tolerate: a cycle, a phase, a bad month. We tell ourselves a story to avoid the fact that we don’t know who we are when we are not planning.

When the curve delivers a shock (a pandemic, a bank collapse, a machine that writes poetry) we refuse to see the vertical wall. We tell ourselves it’s just volatility. A trend. We metabolise awe into utility because the alternative is to admit that the geometry of the world has changed.

The first time we saw a machine summon an image from nothing, it felt like magic. Now we complain about the quality. This is the AI Effect in action: we normalise the miracle to avoid confronting the monster. By refusing to feel the awe, the Treasurer avoids feeling the terror of a machine that evolves twice as fast as our most aggressive historical predictions. They remain calm, solvent, and dangerously unaware that the board they are playing on no longer exists.

Once we stop lying to ourselves about the speed of the car, we must decide who is allowed inside it.

Taste as an Immune System

You cannot organise a flood. You can only seal the hull.

To survive the Infinite Good Enough, we must reclassify taste as a decision rule. Not “do I like this?”, but “does this deserve permeability?” It is no longer a social grace to the vintage, the font, or the reference, but a biological necessity. In a living system, immunity does not ask if a pathogen is ‘interesting’ or ‘potentially useful’. It asks if it is self. If it is not self, it is rejected.

This is the understanding that character dictates destiny. To survive Square Thirty-One, one must follow a set of internal rules: trust the intuition, ignore the naysayers, and never be afraid to fail the expectations of the machine.

The modern web is an engine of uninvited entry. It demands permeability. It wants the email to slide in, the video to autoplay, and the notification to bypass the conscious mind. It treats listening as a transaction rather than an act of presence—the deepest gesture of love where you allow the world (and more importantly, another) to unfold exactly as it wishes.

The Discipline of Omission is the act of closing the pore. It is the cold, jagged refusal to let the ‘mid’ enter the bloodstream. This is not snobbery. It is sanitation. When you decline the viral essay or the meeting without an agenda, you are not missing out. You are deciding that your attention is too expensive to be spent on cheap calories. You are refusing to be a metric in a machine that runs on your exhaustion. You are deciding that if it is not “self,” it does not get to enter.

Solvency on an Exponential Board

We began with the “Still Fine”. It is the sedated state of the linear mind before it notices the vertical wall. Eventually, however, the math always wins. The “Still Fine” inevitably breaks into the “Oh”.

The “Oh” is not a scream. It is the stomach-dropping realisation that you priced your life for scarcity, but the world has flooded you with abundance. It is the moment you realise that “more” is no longer a form of protection, it is a liability.

In this new geometry, we must redefine solvency. Traditional solvency is linear: Assets must exceed Liabilities. Exponential solvency is defensive: Calibration must exceed Exposure.

You are solvent only if your ability to filter the world grows faster than the world’s ability to reach you. If you rely on willpower, you are already bankrupt. The exponential curve of the machine, compounding the world’s information substrate while collapsing the marginal cost of competent output, will always overwhelm the linear curve of human will.

The only winning move is to redraw the boundaries. We reject the Global Board—too fast, too loud, too full of the Infinite Good Enough—and commit to the Small Board. This is elevation, not retreat. It is a decision to operate within a zone of deliberately limited scale where physics still applies, where time moves at the speed of conversation, and where inputs are scarce enough to actually matter. We are not hiding from the world; we are seeking a space for simplicity. We are asking: what can I let go of? Where can I have more space?

The Treasurer looks at the Small Board and sees less. The Curator looks at the Small Board and finds an anchor. They recognise that while we cannot control the future, we can relinquish the fixation on it. By putting away evaluation and opening to what is actually happening, they find a space where life is not what happens to them, but how they react to it.

On Square Thirty-One, the water is rising. The Treasurer tries to drink it, convinced that consumption is how you clear the debt. The Curator watches the flood and decides not to be thirsty.