New Romanticism and Nostalgia

The Fourth Industrial Revolution and the Repricing of Origin

👋🏼 On Monday I’ll be speaking at MIP London’s Attention Economy Leadership Lunch & Mixer. If you’re around, say hi.

Today: We’re living through the Fourth Industrial Revolution. This time we’re not automating factories, we’re automating cognition: writing, music, images, even selection. Each time a new machine reorganises life, culture answers with a recoil. Think Romanticism after the steam engine, Arts and Crafts against mass manufacture, and Wilde’s Aesthetic Movement insisting on beauty over utility. Today, I’m naming our latest counter-move New Romanticism, where provenance, who made it, what’s real, who’s accountable, becomes the new premium.

The Naming of a Feeling

Industrial automation rearranges labour, but its deeper work is the reassignment of meaning.

Each time a civilisation crosses a new threshold of throughput, the machine stops merely raising output and starts shifting the boundary between what is valuable and what is replaceable. It changes what feels authored, what feels owned, what feels true. The terms don’t change politely. They change until you notice, then they change again. When efficiency starts to feel like something taken from you, culture does what it has always done, it recoils. Culture starts reassigning what it considers sacred.

Often this recoil is being misread as nostalgia. Nostalgia is real, and useful. It is one of the mind’s oldest stabilisers. When the present becomes hard to read, memory offers continuity. But nostalgia is often just the wrapper, the feeling that makes a structural change look like something we chose. Underneath that wrapper, something much more coherent is happening.

I’ll call it New Romanticism

New Romanticism is what culture does when “human-made” is no longer the default assumption. When cognition becomes a production line, provenance becomes the premium. You can see the shift in the places where people still pay for what the internet promised to abolish: weight, limits, proof.

In the US, vinyl generated $1.4bn in 2024, nearly three-quarters of physical format revenue, and the highest since 1984. For the third consecutive year it outsold CDs in units: 44 million records shipped versus 33 million CDs1. That is not a hardware trend. Streaming already won distribution. Vinyl is doing something else. It is selling the artefact. An object with edges. An experience you can hold without a platform’s permission.

At the same time, the supply of plausible imitation has become measurable. Deezer says it is receiving over 30,000 fully AI-generated tracks every day, accounting for more than 28% of total daily delivery. It tags that content and excludes it from recommendations2. The pipes are filling. “More content” stops sounding like abundance and starts sounding like noise.

And then the opposite move appears, assuredly, in the places that still sell trust.

Mill Media hit 100,000 readers across its city titles, with 7,000 paying subscribers, built by doing what feeds structurally discourage: original, high-effort work3. Press Gazette reports Mill Media is approaching £1m in annual revenue and that Substack’s 10% fee would represent more than £100,0004. That detail matters because it tells you what has changed: when distribution becomes the whole fight, you start paying for boundaries. You start building a container.

Once you see those three moves together, artefact, flood, bounded voice, you see this “trend everywhere” which is another way to say it’s become a cultural posture.

But why does this matter? When origin becomes ambiguous, responsibility blurs. When you cannot distinguish a human voice from an industrial imitation, it is not only art that gets diluted. It is accountability. It is the ability to say, with any confidence, someone meant this, and therefore someone can stand behind it.

New Romanticism is an attempt to restore those edges.

The recoil pattern

Each time a new machine reorganises life, culture answers with a recoil. Not because people hate progress, but because people hate becoming furniture in somebody else’s system. The recoil is usually misremembered, or at least incorrectly understood in its present moment. Glancing back, the deeper logic is always the same: a defence of whatever the machine has made newly scarce.

In the early nineteenth century, the Luddites are often caricatured as technophobes. They were not. The National Archives frames their protests around unemployment, wage reductions, and a market system reorganising working conditions5. The target was not novelty, but labour regime.

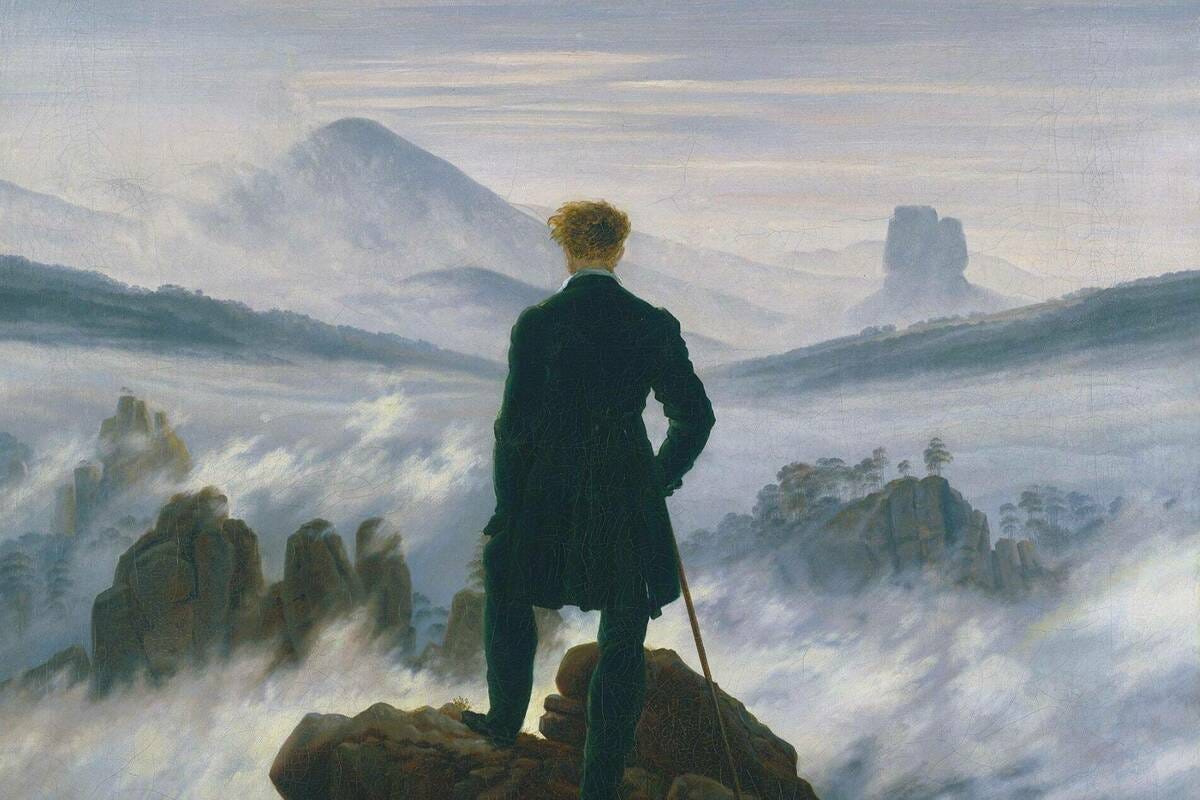

Then came Romanticism, a movement that reads like pure temperament until you remember the context. Romanticism emphasised the individual, the subjective, the emotional, the visionary. It exalted imagination over reason. It treated the artist as a supremely individual creator6. It was not a décor choice. Romanticism was a refusal to accept that a person could be reduced to what could be measured and managed.

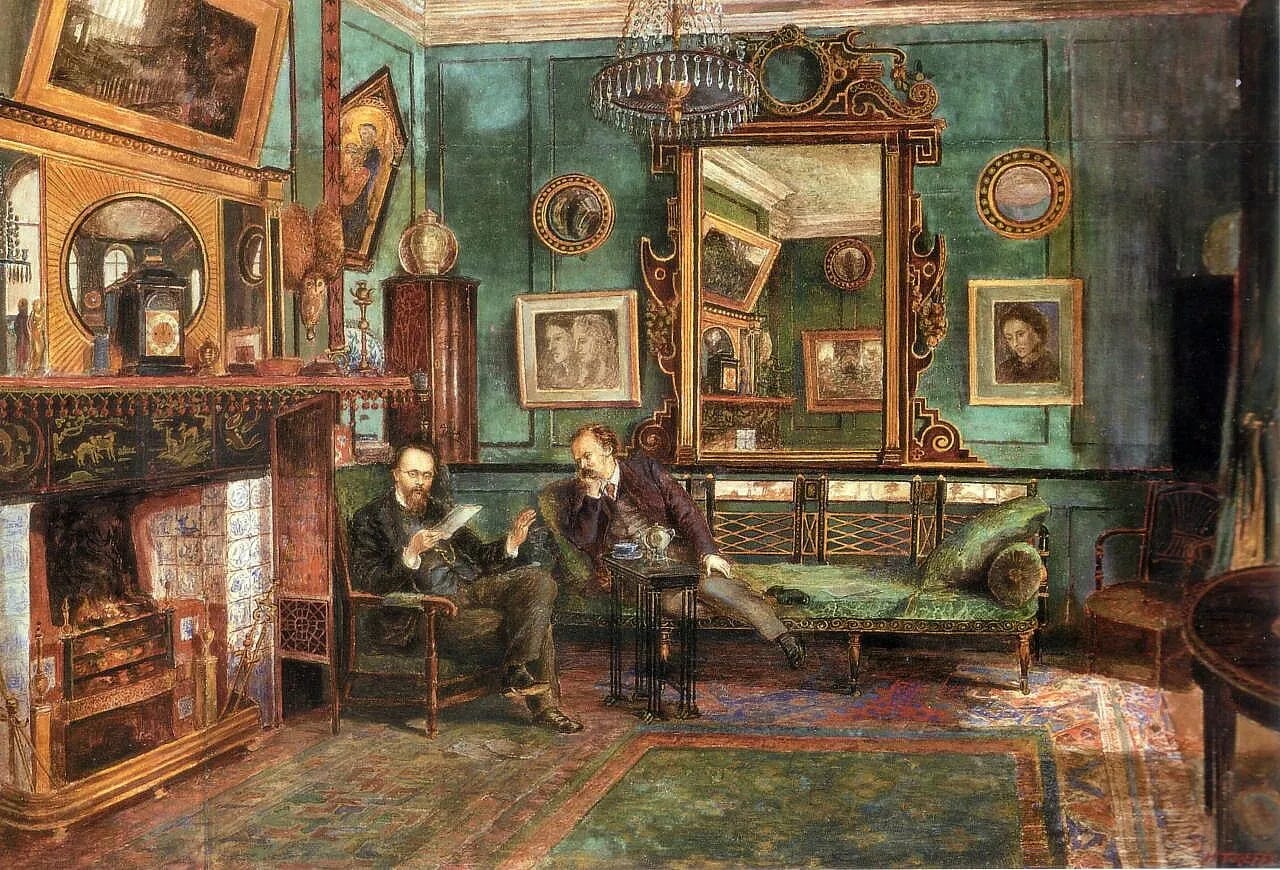

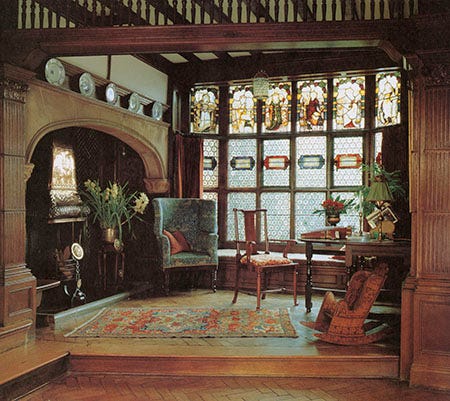

Arts and Crafts hardened that recoil into material form. William Morris cared about wallpaper, yes, but the V&A’s own framing is blunt about what he was really fighting: the division of labour, the severing of maker from product, the loss of pleasure and integrity in work7. Arts and Crafts was not a retreat into handwork for handwork’s sake, but a moral critique of industrial production, expressed through objects that insisted on visible care.

Then came a different kind of refusal, less about labour and more about utility itself.

Aestheticism, the Wildean Aesthetic Movement, argued that art exists for beauty alone, and need not justify itself through politics, morality, or usefulness. Britannica describes it as a reaction against prevailing utilitarian social philosophies and against what was perceived as the ugliness and philistinism of the industrial age8. In other words, when the world tried to turn everything into function, aestheticism insisted that beauty was a value, not a garnish. It was art refusing to be productive.

Romanticism defended interiority. Arts and Crafts defended the maker. Aestheticism defended beauty from utility.

Each recoil protects what the machine makes newly scarce. And now the machine has changed again.

Cognitive automation

The new machine does not stop at automating labour alone and instead extends to imitation and selection. It can manufacture plausible text, plausible music, plausible images at speed, and feeds distribute those imitations with an embedded ease that rarely triggers questioning. The result is not simply more content but an environment in which imitation becomes ambient, constant enough that it changes what it means to recognise a person in a piece of work.

Enter: Walter Benjamin.

Benjamin wrote about aura, the authority of the unique, original work, grounded in presence in time and space. He argued that even the most perfect reproduction lacks the work’s presence, its unique existence where it happens to be9. That used to sound like an art-world problem and now it sounds like Tuesday.

When imitation is effectively infinite, the original stops being a luxury indulgence and becomes something more basic: a stabiliser of trust.

The lemons problem

To understand why New Romanticism feels like more than taste, you need a piece of economics that was never really about cars.

In 1970, George Akerlof published “The Market for ‘Lemons’”, showing how quality uncertainty can degrade markets. When buyers cannot distinguish high quality from low quality, they will pay an average price. High quality exits. Low quality remains. The market does not just worsen, it can collapse under ambiguity10.

That is the logic of lemons: ambiguity is not merely irritating. At scale, it is corrosive.

We are living through the Akerlof moment of human expression.

Once imitation reaches industrial throughput, content stops being culture and starts being inventory. The problem goes from distribution to legibility11.

Akerlof’s paper explicitly notes “counteracting institutions”, mechanisms that arise to make quality legible again12. New Romanticism is culture building those institutions in real time, often without realising it.

The mechanism of provenance scarcity

Provenance used to be a specialist obsession, auction houses, galleries, insurance forms, the small theatre of the certificate. It now belongs in ordinary cultural life. Provenance is the alibi of a work, the verifiable story of where it came from, who made it, what shaped it, what can be checked.

In the modern sense, provenance shows up in four plain places:

Human intention. A work traced back to a specific person, not just a voice but an accountable author.

Physical instantiation. A thing with presence and permanence. You do not buy $1.4bn of vinyl because streaming is unavailable. You buy it because the artefact carries proof of contact with the real.

Editorial edges. Bounded containers that exclude as much as they include: an issue, a dispatch, an edition. Mill Media’s model is instructive here. It is not simply about newsletters, it’s about the limits of a newsletter itself.

Traceable process. Evidence of craft and method, the visible chain of making that reduces information asymmetry.

The scarcity inversion is almost impolite in its simplicity. In the old world, output was scarce and trust was assumed. In the new world, output is effectively infinite, which makes trust the scarcest good in the room.

This is why the lazy reading of nostalgia fails. New Romanticism is not an anti-technology tantrum. It is a cultural system repricing origin under cognitive automation. When style can be imitated at speed, the only thing left worth paying for is the accountable form.

Nostalgia, paperwork, and why the sceptic is wrong

The sceptic’s case is easy to make because it is true as far as it goes. Vinyl, print, anything analogue, it looks like a sentimental retreat.

And we should be fair to that impulse. Nostalgia is a measurable psychological resource. The Tilburg work shows a serial pathway: nostalgia fosters social connectedness, which heightens self-continuity, which strengthens meaning in life13. When the ground shifts, the mind reaches for coherence.

But this is where the sceptic stops thinking too soon. Nostalgia does not require paperwork. Provenance does. If this were only sentiment, we would settle for the look of the old world. Instead we are investing in verification behaviour.

The Authors Guild has launched “Human Authored”, a certification system that defines what counts as human-written, allows only minimal trivial tool use, and backs the mark with a public database where anyone can verify a book’s human origins14.

The European Commission has published a draft Code of Practice on marking and labelling AI-generated content and states that the AI Act’s transparency rules on AI-generated content will become applicable on 2 August 202615.

And the C2PA’s Content Credentials specifications are explicitly designed to tackle what they call the extraordinary challenge of trusting media, with a clear non-goal: they do not judge truth, they verify provenance information is associated with the asset and free from tampering16.

This is provenance moving from taste to infrastructure.

This is also the deepest reason to care. When origin becomes ambiguous, responsibility blurs. Verification is not a lifestyle preference but the beginning of accountability.

The name, earned

New Romanticism is the cultural recoil to cognitive automation. It is the repricing of provenance in a world where imitation is ambient and “human-made” is no longer the default assumption.

It looks like artefacts. It looks like bounded voices. It looks like paperwork.

It is not a retreat into the past. It is a defence of the conditions that make meaning possible in the first place. This is what happens when provenance becomes scarce.

Call it New Romanticism.

Deezer’s decision to tag and exclude fully synthetic tracks is a countermeasure, which is another way of saying the trust problem is now a product problem. (Deezer Newsroom)