The Attention Economy: How Collapse Became a Business Model

Pt 1: When education, housing, and labour broke, attention became the only asset left.

Welcome to Part I of a 3-part series on the Attention Economy.

I’m going to say something controversial: The Attention Economy has nothing to do with being addicted to our phones.

I’m going to argue something more controversial: It emerged because the foundational inputs of the old economy—education, housing, labour—stopped producing outcomes, and the institutions meant to fix that failure—higher education, policy, finance—started monetising it instead1.

Progress hasn’t slowed, it’s stopped: quietly, systemically. And in the vacuum left behind, something else took its place.

Attention rose as the last viable asset for those without capital — and was quickly weaponised by those who already had it.

And just as this new system has come to play, generative AI has also arrived—not as the cause, but the accelerant. AI collapses the cost of creation, floods the zone with infinite output, and makes perception—not production—the scarcest resource on Earth. If attention was already the substrate, AI made it the battleground.

This is the new operating system. It’s not a media trend or generational quirk. It’s a full-stack replacement for a model that broke and never got fixed23. Most haven’t named the system. Most are still trying to win a game that no longer exists.

This series exists to map what replaced it.

What We’re Covering in This Series

Part I — What Broke, What Replaced It (You’re here.)

Part II — The Attention Stack: Infrastructure for a New Economy: We decode the machine behind the headlines:

Why OpenAI, MrBeast, Trump, and Musk run structurally identical models4

How markets, platforms, fandoms, and politics all now operate on one logic:

Attention → Narrative → Speculation → Capital

The 10 operating laws of the Attention Economy, a ruleset for how power behaves now

Part III — Meaning Collapse: Who Wins, What Breaks, and How to Reroute: We name the cost:

Why frictionless design makes you feel hollow

Why coherence is now a privilege, not a baseline

Why attention extraction is now ecological as well as psychological

How full-stack operators turn your clicks into capital, and what it means to design for durability, not just velocity

Subscribe now to get Parts II and III. Because if you don’t understand this system, you’re not navigating it, you’re being shaped by it.

Today We’re Talking About

Why the old system broke, mathematically: We map the collapse of the postwar economic formula from student debt (+240%) to housing inflation (+121%) to gig precarity, showing why progress is no longer statistically probable5.

How institutions monetised failure: Universities scaled admin, not education. Policy became PR, not remedy. Finance taxed labour but rewarded wealth. Collapse wasn’t corrected, it was commodified.

Why the Anglosphere collapsed hardest: Gallup and the FT confirm it’s not the same everywhere. It’s a structurally unique and accelerated failure of English-speaking economies built on market liberalism and personal hustle.

What filled the vacuum: With no path to stability via credentials or labour, attention emerged as the last extractable input, unregulated, compounding, and globally tradable.

Why Gen Z didn’t give up, they retooled: When capital disappeared and trust broke, they pivoted to presence. Social graphs became distribution. Meme fluency became strategy.

How the Creator Economy became economic infrastructure: With 250M participants, 50M full-time, and $520B projected market size, creator labour is no longer fringe. It’s the macroeconomic reroute.

What’s being extracted now: Not just time or clicks, but cognition, emotional bandwidth, interpretive capacity, and coherence. You may think you’re producing, but you’re really being processed.

Why AI is the accelerant, not the cause: Generative tools collapsed the cost of creation and made attention the last moat. Narrative became the new scarcity and coherence, the first casualty.

The Collapse of Predictable Progress

Before we can map the architecture of the Attention Economy, we have to name what it replaced.

For most of the 20th century, the promise was simple: study hard, work consistently, and you’d rise. The system would meet you halfway. Economic mobility wasn’t guaranteed, but it was statistically probable. Progress had a rhythm. Generational outcomes, while uneven, still trended upward.

That rhythm is now mathematically impossible.

This isn’t recent decay — it’s the compounding failure of systems that began breaking in the 1980s and were papered over by debt, gigification, and distraction.

Student Debt

In 2006, total US student debt sat at $520 billion. By 2024, it passed $1.77 trillion6—growing more than twice as fast as U.S. nominal GDP from 2006-2024. The average borrower now carries over $37,000 in educational debt7.

From 2006 to 2024, nominal US GDP rose by 95%. Student debt rose by 240%. The economy slowed and the promise of mobility stalled. But the financialisation of higher education didn’t get the memo — it only accelerated. Tuition rose, wages stagnated, and debt became the substitute for progress.

Housing Access

Since 2006, US median home prices have risen +121%. Median household income has grown only +36%8. What was once a 3.3× affordability ratio has become 6.1×—pricing out not just ownership, but the basic premise of financial independence9.

In 2006, buying a house was tight, but technically survivable. By 2023, we’re at “just move to Ohio” discourse. What was once a symbol of stability is now an asset class for the already-asseted. Ownership is now a speculative prize, not a social contract.

Degree ROI

Across the US and UK, the wage premium for a university degree is steadily declining, especially when adjusted for tuition debt, inflation, and delayed entry into the job market. Credential inflation has outpaced yield, creating a system where degrees are more expensive and less effective at guaranteeing upward mobility10.

From 1990 to 2008, the bachelor’s degree still delivered. The wage premium for college grads rose from baseline to +28% relative to high school graduates, peaking at an index value of 128.

But then the curve stalls. And in the 15 years that followed, it slid back down to 115, a 13% decline from its peak. Not catastrophic but certainly fatal for the narrative.

Now layer in the rest of the equation:

US college tuition has risen 180% since 2000.

Average student debt sits at $37,000+ per borrower.

Real wage growth has slowed across nearly all sectors.

You’re paying triple, waiting longer, and earning marginally more, if at all.

This isn’t about Gen Z being lazy. There is no math to make this add up. You now spend a decade repaying a signal that no longer guarantees you entry.

Platform Labour

Over 60% of gig workers earn below minimum wage11 when expenses are accounted for. The “freedom” of flexible work is largely a euphemism for structural precarity: no benefits, no protection, and no path toward security12.

The “liberation” of workers was simply offloading risk. The gig economy was sold as autonomy, but for most, it’s untenable. And you’re looking at a labour system that’s been structurally unbundled. The platform takes the value and you take the volatility.

“The Affordability Crisis” Is a Smokescreen. This Is Structural Collapse.

Politicians love to break it into parts: a housing issue here, a student debt problem there, a tight labour market somewhere else. But this isn’t a series of isolated symptoms. It’s a systemic failure. The foundational inputs of the old economy — education, housing, and labour — no longer yield the outcomes they promised.

So no, you’re not behind. You’re simply realising doing everything right no longer produces anything stable.

But that’s only half the breakdown. Because even as the core inputs failed—housing, labour, education—the institutions meant to intervene didn’t just stand still. They adapted to the collapse, profited from it, and helped calcify it.

Institutional Failure

The institutions meant to intervene—universities, governments, financial systems—have instead entrenched the collapse.

Higher Education

Universities were once engines of upward mobility. Today, they are debt-loading credential mills operating under the pretence of future yield.

US university tuition has risen nearly 180% since 200013—more than any other major category of consumer spending14.

Administrative staff growth in higher education outpaces faculty hiring by nearly 2:1, diverting funding toward institutional scale rather than student outcomes15.

The content of education—especially in Anglosphere nations—has failed to keep pace with automation, AI, and globalised labour demands.

Universities scaled bureaucracy, not education. The result? Degrees got more expensive, less useful… and institutions profited anyway.

Degrees have become symbols of selection, not guarantees of preparedness. And yet: the cost keeps rising, because institutions are rewarded for enrolment volume, not graduate outcomes.

Policy as Optics, Not Remedy

Public policy has responded to this collapse not with structural reform, but with incremental PR manoeuvres:

In the US, debt forgiveness has been limited in scope and subject to repeated legal reversal.

UK policy has focused on housing benefit adjustments and mortgage gimmicks rather than confronting zoning policy, land hoarding, or speculative development.

In Canada and Australia, inflationary pressures have been met with rate hikes that disproportionately punish wage earners while protecting asset portfolios.

The result is political theatre designed for electoral optics, not functional correction. And the outcomes speak for themselves.

Between 2018 and 2023, wages in the US, UK, Canada, and Australia rose by single digits to low teens. But asset values, especially housing and equities, surged by 35–43%. The people earning are being outpaced by the people already owning.

Policy hasn’t narrowed this gap, only widening it by protecting portfolios, not paychecks.

The issue isn’t that assets grew, it’s that labour didn’t.

Asset growth, in itself, is not the problem — in fact, wealth creation should be encouraged. But when systems are designed to reward existing wealth while penalising new effort, mobility collapses.

The goal isn’t to punish asset holders but to ensure that those without assets still have a path to participation — not just as renters, borrowers, and freelancers, but as owners, builders, and stakeholders.

A functioning economy rewards both labour and capital. What we’ve built instead is a system that compounds wealth for the already-asseted and offers volatility to everyone else.

Across the Anglosphere16, asset prices soared while wages stagnated. In the US, UK, Canada, and Australia, housing wealth grew 3–5× faster than income. Instead of fixing the system, governments tweaked it for headlines: loan gimmicks, benefit caps, interest rate shocks.

Government is no longer the arena for redistribution. It’s a reactive comms engine, built to manage public anxiety while preserving structural imbalance.

Finance and the Asset Capture Machine

Financial systems, meanwhile, have evolved to reward those who already hold equity—whether in homes, stocks, or companies—and penalise those trying to earn their way in.

Between 2010 and 2023, global asset inflation outpaced wage growth by 3–5× in most Anglosphere economies17.

Capital gains receive more favourable tax treatment than income across nearly all of them18.

Access to wealth creation is now contingent on preexisting wealth—down payments, liquidity, credit ratings—don’t work.

In every major Anglosphere economy, capital gains are taxed significantly less than labour despite both generating income. In the UK, someone flipping property can pay the same or less than a teacher on PAYE. In the US, a hedge fund manager can pay less than their assistant.

Finance has shifted from enabling opportunity to entrenching advantage. If you work for your money, it’s taxed. If your money works for you, it compounds and then is later taxed at a reduced rate. The result? A recursive system of asset capture:

Money → Assets → Value → More Money.

And labour? Labour is just the delay mechanism in between.

Put together, these institutions haven’t just failed to fix the collapse but stabilised it in their favour19.

What began as a breakdown in the foundational inputs — education, housing, labour — has been matched, managed, and monetised by the very systems meant to respond. Universities sell debt instead of mobility. Policy tweaks symptoms to avoid touching causes. Finance captures value not by creating, but by compounding what it already owns.

The collapse becomes infrastructure when what used to be an engine of mobility is now a bureaucracy of managed decline. Stasis over growth. Optics over outcomes.

Institutions don’t build capacity for everyone anymore and now (have to) ration it. And in doing so, they’ve quietly rerouted their role from stewards of progress to administrators of precarity.

It’s no wonder there’s no faith in institutions.

A Collapse Concentrated in the Anglosphere

This is a more geographically precise collapse than anyone would like to mention20.

According to the Financial Times, the steepest declines in mental health, economic trust, and belief in progress are not evenly distributed across OECD nations. They are concentrated in five countries21:

The United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand — the Anglosphere22.

These nations share language and ideology, but they also share a structural design flaw: a legacy of hyper-market liberalism that tied social mobility to asset accumulation, then priced the next generation out of those assets.

The result?

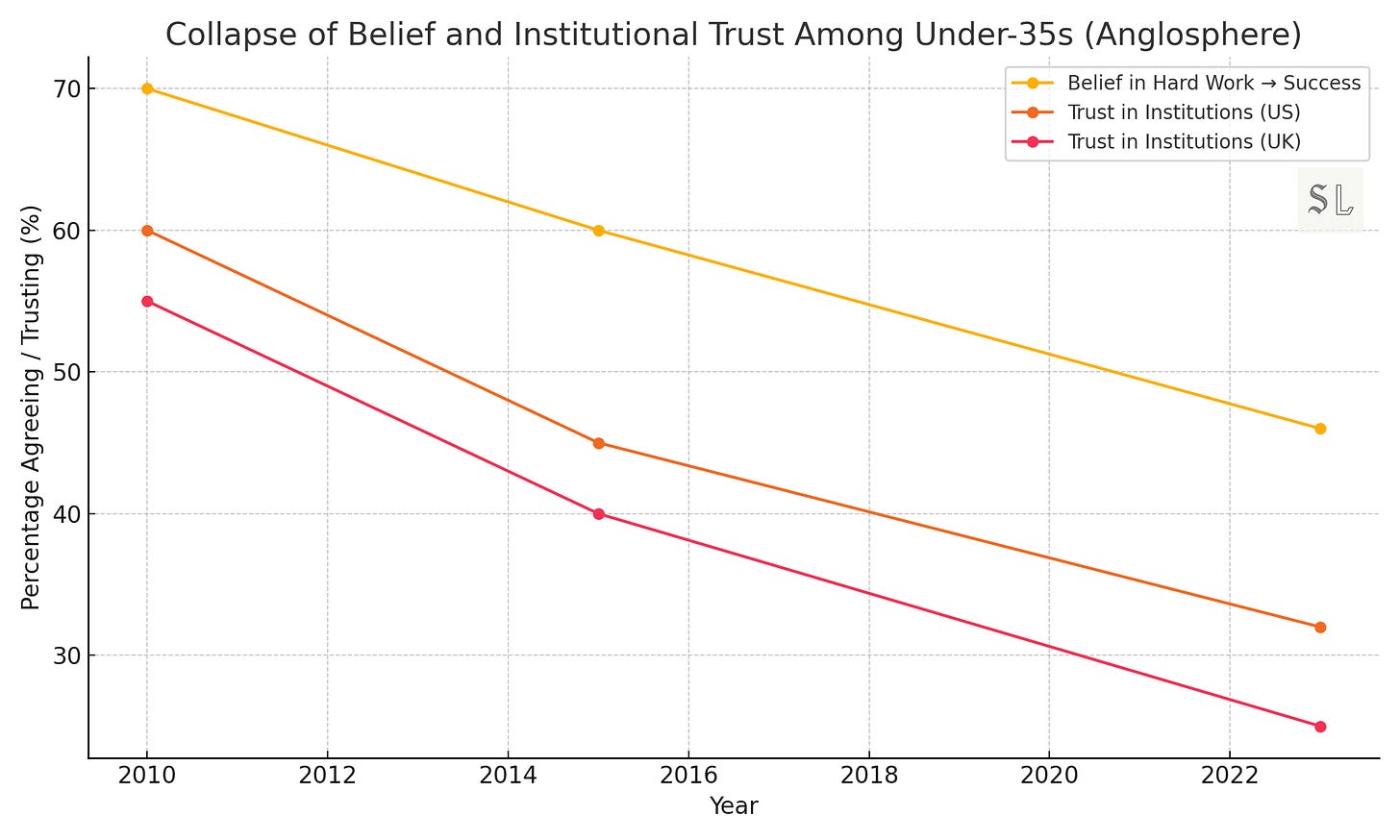

In the US, belief in “hard work leads to success” has dropped precipitously among adults under 35.

In the UK, trust in the idea that institutions exist to serve public good has fallen below 25%.

Across all five countries, young adults are now statistically less hopeful, less trusting, and more anxious than their counterparts in France, Germany, the Nordics, or Japan.

Even nations facing similar inflationary pressures—like Spain or Italy—didn’t report the same generational collapse in perceived possibility. The FT calls it plainly: The crisis of youth despair is not global. It is a uniquely English-speaking collapse23.

What we criticise as generational fragility or laziness is actually the logical outcome of our societal structure.

Where other countries invested in public housing, healthcare, education, or wage floors, the Anglosphere relied on market signals and personal hustle to deliver outcomes that were once public goods.

So, what we deride as generational entitlement is actually better described with data. The younger generations didn’t stop believing in the future, it’s just that the future stopped being offered to them.

Belief Breaks First

Economic systems do not collapse by numbers alone.

Before labour loses traction, before debt outpaces growth, before platforms cannibalise institutions—belief cracks. The sense that effort translates into mobility, that systems reward participation, that your time and energy accrue toward anything—once that’s gone, it doesn’t return easily.

Gen Z no longer believes in the formula: degree → job → house → upward mobility. As Kyla Scalon puts it, “The labor market…less like a ladder, more like a slot machine.”

Hope hasn’t evaporated as much as been disproven.

Institutional trust has gone from erosion to inversion.

Young people now report higher visibility into collapse—they’re more informed, more sceptical, more literate in systemic dysfunction—without any corresponding belief in reform.

According to the Gallup World Poll (as reported in the Financial Times, 2025), belief that “hard work leads to success” has dropped from around 70% in 2010 to just 46% in 2023 among under-35s in the US, UK, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.

This is statistically visible (and verifiable) disillusionment.

At the same time, institutional trust has cratered. In the US, Pew Research Center finds that trust in major institutions among adults under 30 has fallen from 60% in 2010 to just 32% in 2023. In the UK, Gallup + FT reporting shows a similar collapse — trust in public institutions among under-35s now sits below 25%.

Where trust once grounded participation, its absence now accelerates exit

A generation has watched the rules change mid-game and has recalibrated accordingly.

The lack of trust removes optimism and rewires logic. As Alex Tabarrok notes, “The more people believe that wealth, status, and well-being are zero-sum, the more they back policies that make the world zero-sum.24” The result is ideological regression masked as survival: when the pie no longer grows, every other person becomes a threat to your slice. Economic collapse evolves into a psychological reprogramming of what’s possible, what’s fair, and what the future even means. Hello, populism, aggression toward immigrants, gender scapegoating, and algorithmically fuelled identity wars. People aren’t evil, they’re just reframed as competition.

What Replaced It: Attention as the Last Viable Asset

When capital became inaccessible, institutions un-reformable, and labour unscalable, attention emerged as the only viable input left — unregulated, real-time, and globally tradable25.

It required no credential, no permission, and no legacy infrastructure. If you had presence, you could generate visibility. If you had coherence, you could build belief. If you could build belief, you could raise capital.

In a post-progress economy, focus became the new currency and the only lever still within reach.

In what Kyla Scanlon calls a “zero-sum casino economy,” the disappearance of predictable paths has produced a system where “algorithms mediate our worth and artificial scarcity is optimised for someone else’s profit.”

At work, it’s sending out 200 applications and getting ghosted — your AI-generated CV rejected by an AI gatekeeper. At home, it’s styling your rental like a Pinterest board — while knowing your landlord won’t let you paint the walls, hang shelves, or ever fully nest at home. In sex and dating, it’s swiping for intimacy and drowning in comparison. Financially, it’s hustling longer for shrinking returns while watching meme coins mint millionaires. Spiritually, it’s losing the thread of who you are because every part of life now feels like a pitch deck.

The casino isn’t just economic, it’s existential. And no one’s holding the house accountable26.

The Pivot to Attention

Gen Z didn’t “give up.” They watched the inputs stop working—labour, credentials, asset access—and moved toward the only one they still controlled: attention27.

When job ladders disappear, social graphs become distribution networks.

When CVs lose signalling power, platform literacy becomes career currency.

When capital access dries up, memetic fluency becomes economic strategy.

This is the beginning of a new value logic: not what you build, but what you can direct attention toward, amplify through narrative, and scale through speculation. And it isn’t just happening on the margins, but instead on the main stage as the macroeconomic event.

The Creator Economy: Not a Hobby — a Reroute

Today, more than 250 million people participate in the creator economy. Over 50 million of them do it full-time28. That’s a workforce larger than manufacturing in most G20 countries.

Market size in 2024: $250 billion

Projected value by 2027: $520 billion29

People aren’t (necessarily) chasing virality for fun but monetising the only remaining surface area where agency is still possible30.

What is termed influencer culture might actually be better defined as post-institutional strategy.

The side hustle has scaled into a parallel economy and in that economy, the core asset isn’t product, pedigree, or even ownership. It’s audience. Attention. Distribution. And the ability to turn visibility into velocity—across platforms, brands, causes, companies, and selfhood.

This is the upstream layer of the Attention Stack31. And from there:

That’s the stack. But stacks don’t emerge from nowhere. They emerge from resource shifts. And in every era, the dominant resource is the thing most worth extracting.

From Labour to You: The Extraction Arc

Every economic era has its prized input. That input is what gets scaled, regulated, harvested, and eventually sold back to you. Progress is never neutral. It’s a story of extraction and who gets extracted.

First, they took your labour.

You clocked in. You produced. Your time was your wage. Industrial capitalism ran on body-hours: manufacturing, mining, manual output. The system wasn’t subtle. It didn’t need to be. You worked a double shift at the factory. You stacked boxes until your knees gave out.

Then, they took your ideas.

The knowledge economy arrived with cubicles and KPIs. Suddenly, creativity became productivity. Your innovation was IP. Your thoughts were corporate assets. Welcome to the brainstorm-as-commodity era. You pitched a campaign in a team meeting that became the client’s new tagline. You stayed late refining a deck that someone else presented.

Next, they took your data.

The platforms promised frictionless connection. What they delivered was surveillance capitalism. Your clicks, your searches, your preferences — turned into training data, ad auctions, and algorithmic profile fodder. You Googled “burnout symptoms” and got served a wellness ad. You posted a “new you” selfie and trained a model.

And now? They take you.

Not your labour, not your ideas, not even your metadata… You.

Your attention, your cognition, your ability to focus, to interpret, to know what’s real, and your sense of self across time.

You spent more time curating your wedding photos than being in them. You kissed like you were being watched. You used to dream about the future — now you optimise for the feed.

What matters now isn’t what you produce. It’s what you can be made to see, feel, believe, and repeat. The feed doesn’t want your content. It wants your infrastructure.

And the wild part? You give it away — every scroll, every share, every “lol.” Not because you’re lazy. Because the system has been exquisitely engineered to feel like participation while functioning as extraction.

You’re not a user. You’re a renewable cognitive resource with a screen addiction and no union32.

This is what attention capitalism actually means. Not ads. Not dopamine.

Harvesting your capacity to make meaning, then monetising it without your permission33.

And the better you are at keeping up, the more you get mined.

What’s Being Extracted Now

Let’s be precise about the asset class.

Time: Not just in total hours, but in scroll depth, retention rates, and real-time behavioural drift.

Cognition: Focus, interruption tolerance, the ability to hold complex thought without push notification fracture.

Emotional Bandwidth: Rage, hope, aspiration, FOMO. The monetisation of affect in feedback loops.

Interpretive Muscle: Your ability to sort real from fake, signal from noise, narrative from chaos.

Coherence: The internal thread that says: this is who I am, this is what I believe, this is what matters. That thread is what’s now being split, retargeted, and sold.

But collapse doesn’t just affect belief, it warps time. Without shared milestones like homeownership, pension thresholds, or stable career arcs, there’s no longer a reliable clock to synchronise adult life. Everyone is moving, but on different timelines: renting at 40, parenting at 20, freelancing at 65. The rhythm that once created societal coherence has fractured into personal chaos. Time has become ambient, nonlinear, and deeply privatised. The future now arrives as algorithmic volatility, not linear progression34.

This is active participation in your own commodification, not passive consumption. Platforms extract your architecture — your ability to process, perceive, and persist as a stable subject.

And this is the moment we stop calling it “engagement” and start calling it what it is: extraction.

This is shadow work at scale. The kind Ivan Illich warned us about35 — invisible, unpaid, and increasingly cognitive. You’re not just maintaining a household or managing bureaucracies, you’re editing your selfhood, captioning your intimacy, tending to your algorithmic reflection. And none of it gets paid. The Attention Economy hasn’t just repackage labour, it’s outsourced emotional, reputational, and relational upkeep to the individual, then called it empowerment.

Attention as Infrastructure, Not Afterthought

In a previous economy, attention was the bonus. You built the thing. Then you earned attention. If it was good enough, you might even get some press.

That’s over.

Attention is the prerequisite and no longer the reward. You don’t get attention after you make something. You get funded, hired, elected, or believed because you already have it36.

Visibility no longer follows legitimacy, it manufactures it. Narrative doesn’t trail delivery and instead determines whether delivery happens at all37. Marketing used to be downstream of strategy and now is the strategy. This is the infrastructure-level shift no one in boardrooms wants to say out loud:

If you can’t capture attention, your product won’t launch, your campaign won’t scale, your IP won’t get funded, and your value won’t exist in the eyes of the market. It doesn’t matter if it’s brilliant, it doesn’t matter if it works. In this economy, attention is existence. And if you’re not building for it, you’re invisible.

And how does AI relate to all of this?

It’s only getting starker38. AI didn’t start the fire, but it poured fuel on it — collapsing the cost of creation, flooding the zone with infinite output, and making perception—not production—the rarest commodity left.

In a world where anyone can make anything, making something no longer confers value. What’s scarce now is not production, but perception. The only thing you can’t automate is someone choosing to pay attention.

You’re Not Burned Out, You’re Operating in a New Economy

If you’ve felt disoriented, fogged out, strangely behind despite working harder than ever — it’s not a failure of effort39. You’re still calibrated for an economy that promised mobility for labour, security through credentials, and legitimacy through institutions. But that economy doesn’t exist anymore.

The ladder’s gone and so is the map.

And here’s where it becomes existential. In the absence of institutional feedback, human validation has been quietly outsourced to algorithms. It’s not just about getting hired, going viral, or raising a round — it’s about proving you exist in a system that no longer mirrors anything back. Coherence used to be socially affirmed and now it’s scored. When identity is mediated through metrics, and survival depends on visibility, you’re not just working, you’re continually requalifying for value.

Algorithms have quietly replaced institutions as the primary feedback loop for what’s worthy, real, or true. They don’t govern through law, but through ranking. They don’t ask what’s just, only what’s engaging. And when attention becomes the regulator of meaning, coherence gives way to performance. You’re not becoming who you are, you’re becoming what performs.

If attention is the new oil, you’re either drilling or you are the field. And most people haven’t been told they’ve already been leased.

Coming Up: Part II — The Attention Stack

Now that we’ve named what collapsed (and what replaced it) we move to the mechanics.

Attention → Narrative → Speculation → Capital

In Part II, we’ll break down the full logic stack of the new attention-first economy:

Why narrative is now the most powerful form of leverage

How creators, founders, politicians, and platforms are all running the same playbook

And why the most valuable asset in the modern economy is not output, but belief

This isn’t generational exceptionalism, it’s structural. According to the U.S. Department of Education and the Education Data Initiative, the cost of college has risen 180% since 2000, while wage growth has lagged far behind. Simultaneously, median home prices have doubled relative to income, and over 60% of gig workers earn below minimum wage after expenses (Fairwork Project, 2023). The argument is not that Gen Z is uniquely fragile, but that they are the first generation for whom the formula of effort → stability has been statistically invalidated.

Yes, it rhymes with late capitalism — but this isn’t just about inequality or decline. What’s new is the operating logic: attention as the upstream asset class, narrative as economic engine, and speculation as standard protocol. This is a system where value formation itself has been restructured — not just redistributed.

This isn’t a lament for a lost golden age — it’s an attempt to map the new rules. Capitalism evolves through inflection points: industrialisation, financialisation, platformisation. The Attention Economy is another such shift. But what makes this one distinct is its opacity — no one announced the transition, yet everyone’s operating inside it. And without a map, the system defaults to extraction.

These aren’t anomalies. They’re early signals. Extreme examples help clarify systemic logic: valuation is no longer tethered to fundamentals but to perceived inevitability. That’s why seemingly divergent actors — from creators to politicians to founders — are all rewarded by the same input: narrative velocity and belief coherence. They show how the Attention Stack functions in its purest form.

The “old economy” was never structurally inclusive. Women, people of colour, LGBTQ+ individuals, and many disabled workers were often excluded or exploited. This essay does not romanticise that era. Instead, it highlights how even its flawed promises — like the potential for generational progress — have now collapsed, leaving behind not a more equitable system, but a structurally incoherent one that offers no viable roadmap for anyone.

U.S. Department of Education; Education Data Initiative

Federal Reserve Bank of New York; US Department of Education, 2024. Reported in “The Growing Student Debt Burden and Its Economic Implications.

S&P Case-Shiller Home Price Index; U.S. Census Bureau income data

US Census Bureau & Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED), 2006–2023. As compiled in “Median Home Price and Household Income Trends,” Urban Institute, 2024.

Institute for Fiscal Studies (UK), 2023; Georgetown Center on Education and the Workforce, 2024. See also OECD Education at a Glance, 2023.

Fairwork Project, Oxford Internet Institute, “Ratings 2023: Labour Standards in the Platform Economy,” 2023. See also: Economic Policy Institute, “The Gig Economy and the Future of Work,” 2023.

Economic Policy Institute, “The Gig Economy and the Future of Work,” 2023. See also Fairwork Project, Oxford Internet Institute, 2022.

Education Data Initiative; College Board. Source: Education Data Initiative, 2024.

US Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Price Index (CPI) Data, 2023; College Board ‘Trends in College Pricing,’ 2023.

The Delta Cost Project (American Institutes for Research), “Trends in College Spending,” 2021–2023.

See: OECD Tax Policy Studies No. 29, “Taxation of Household Savings,” 2023 which shows that across Anglosphere economies, labour income is taxed more heavily than capital gains, discouraging earned upward mobility while subsidising passive accumulation.

OECD Economic Outlook, 2023; Bank of England Financial Stability Report, 2023; US Federal Reserve Survey of Consumer Finances, 2022.

OECD Tax Policy Studies No. 29, “Taxation of Household Savings,” 2023; HM Treasury (UK), “Tax Reliefs Evaluation,” 2022; US Congressional Budget Office, “Distribution of Federal Tax Expenditures,” 2023.

Institutions haven’t disappeared — they’ve become decoupled from their promised outcomes. Universities still confer degrees, but with diminished ROI. Finance still offers products, but mostly to the asset-rich. Policy still reacts, but often at the level of optics, not structure. This essay critiques outcome erosion, not institutional existence.

The decline in global absolute poverty — especially across parts of Asia and sub-Saharan Africa — is real and critical. This essay does not refute those gains. It specifically addresses the collapse of economic predictability and upward mobility within advanced Anglosphere economies (U.S., U.K., Canada, Australia, New Zealand), where inflation-adjusted wages have stagnated, debt has soared, and belief in progress has measurably eroded — especially among under-35s. See: Financial Times (2025), Gallup World Poll, and World Happiness Report.

The Attention Economy is a global phenomenon — but its underlying fuel differs by region. This essay focuses on the Anglosphere because it’s where economic inputs failed fastest, institutional trust collapsed hardest, and belief in mobility decayed most visibly. Other economies may experience similar shifts, but from different starting points and at different speeds.

Burn-Murdoch, John. “Why are young adults in the English-speaking world so unhappy?” Financial Times, July 25, 2025. Gallup World Poll & World Happiness Report data.

This doesn’t imply that youth in other countries aren’t facing hardship, only that the structural pattern of collapse shows greater severity and specificity in the Anglosphere. OECD, Gallup, and World Happiness Report data all show that declines in economic trust, mental health, and belief in progress are statistically sharper in the US, UK, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand compared to peer economies like France, Germany, and Japan. This piece focuses on that pattern not out of parochialism, but because it is measurable and systemically distinct.

Tabarrok, Alex. As quoted in Kyla Scanlon, “Zero-sum Thinking and the Labor Market,” Substack, July 23, 2025.

This isn’t just temporal correlation. The argument rests on structural substitution: when credentialism, capital access, and institutional trust broke down, attention became the only generative lever that remained accessible and scalable, especially in the context of a deregulated digital economy. The rise of attention as infrastructure is causal in that vacuum, not merely coincidental.

This doesn’t mean no one succeeds. But success has become exception, not expectation. The attention economy, like previous systems, produces winners — but it no longer offers a stable or replicable path. Today’s upward trajectories are non-linear, memetic, and algorithmically contingent — far more lottery ticket than ladder. See: Markovitz, D. (2023). The Myth of Meritocracy in the Attention Economy, Yale Law Review.

This shift isn’t a rejection of ambition, it’s a reallocation of it. The rise of the creator economy (valued at $250B in 2024 and projected to reach $520B by 2027, per Goldman Sachs) shows how new forms of leverage have emerged. But they didn’t emerge in abundance, they emerged from collapse. For most creators, the pursuit of audience is not elective but adaptive: a way to regain economic agency in a system where traditional paths no longer offer upward mobility.

SignalFire, Creator Economy Market Map, 2023. SignalFire’s estimate used in investor decks and validated by Meta, Adobe, and Shopify platform data.

Goldman Sachs Research, The Creator Economy: Unlocking the Next Wave of Digital Monetisation, 2023. Cited in multiple industry reports and supported by SignalFire and Statista estimates.

This isn’t to suggest the Creator Economy is equitable or universally accessible — it isn’t. It’s deeply shaped by platform incentives, visibility hierarchies, and monetisation barriers. But for tens of millions, it has become the only route with any remaining surface area for self-direction. The argument here isn’t about idealising the system, but recognising it as a dominant structural response to institutional failure.

As economic mobility disappeared, prestige mobility took its place. In a world where assets are out of reach, symbolic capital becomes the default lever. What used to be markers of status — degrees, titles, homeownership — are now replaced with followers, aesthetic literacy, and meme fluency. You may not own the house, but you curate the feed. You may not have a pension, but you have a podcast. The shift isn’t delusional, it’s adaptive. When upward mobility collapses in material terms, we reach for its narrative counterpart. It’s not hustle culture as much as class signalling through story. Bourdieu, Pierre. “The Forms of Capital.” In J. Richardson (Ed.) Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education (1986): 241–258. See also: Han, Byung-Chul. “The Burnout Society.” Stanford University Press, 2015.

This critique focuses on systemic incentives, not individual outcomes. Attention can be wielded strategically — for community-building, storytelling, or self-authorship. But structurally, most systems are designed to harvest attention before rewarding it. Exceptions prove possibility, not norm. See: Zuboff, S. (2019). The Age of Surveillance Capitalism.

And the system doesn’t just mine your attention metaphorically, it runs on literal extraction, too. The physical infrastructure required to fuel generative AI, infinite scroll feeds, and platform-scale video demands vast energy and resource inputs. According to the IEA, global data centre electricity consumption could double between 2022 and 2026, reaching 1,000 terawatt-hours per year, roughly the annual energy use of Japan. AI training alone may account for a quarter of that by mid-decade. Meaning: the more we scroll, post, prompt, and push content, the more we burn. The Attention Economy doesn’t just exhaust people, it also exhausts the planet. International Energy Agency (IEA), “Electricity 2024: Analysis and Forecast to 2026.” Published February 2024. See also: “AI’s Growing Appetite for Power,” Financial Times, March 2024.

See: Jonathan Crary, 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep (Verso, 2013); also: Judy Wajcman, “Pressed for Time: The Acceleration of Life in Digital Capitalism,” University of Chicago Press, 2015.

Ivan Illich first outlined the concept of “shadow work” in Tools for Conviviality (1973) and later expanded on it in Shadow Work (1981). He described it as the invisible labour required to maintain participation in modern economic systems — from self-service tasks to the cognitive burdens of navigating bureaucracies. See also: Craig Lambert, Shadow Work: The Unpaid, Unseen Jobs That Fill Your Day, Counterpoint Press, 2015.

This doesn’t mean execution, skill, or substance no longer matter. It means they’ve been displaced as the starting point. In a market oversaturated with output — and accelerated by AI — attention now functions as the filtration layer through which all value must pass. Quality work still wins. But it can’t win if it’s never seen.

This doesn’t mean fundamentals are dead — only deferred. In an attention-first economy, the order of operations has changed. Visibility creates belief; belief unlocks capital; and only then do fundamentals get to prove their worth. The risk isn’t that companies don’t need substance. It’s that they may never need to get there if the narrative delivers a high enough return.

Generative AI has collapsed the cost of content, but it hasn’t increased its value. When visuals, voiceovers, and storylines can all be generated at scale, narrative becomes the only defensible moat and the primary arena of competition. But this doesn’t just raise the stakes, it dilutes the field. With every brand, creator, and platform flooding the zone with strategic storytelling, the collective output starts to cancel itself out. The result is narrative saturation: too much meaning, too fast, with too little friction. And when meaning floods, coherence drowns. See: McKinsey Global Institute, “The Economic Potential of Generative AI: The Next Productivity Frontier,” 2023; also: Benedict Evans, “Content, Commoditised,” 2024.

This doesn’t deny progress. It clarifies who benefits. Technological abundance has accelerated, yes, but so has inequality in who can convert it into stability. AI, remote work, and low-friction tools expand what’s possible, but they don’t solve for systemic precarity. When access improves but security collapses, the result is speed without safety. This essay doesn’t argue against innovation, it argues that without corresponding investment in economic infrastructure, innovation becomes a performance trap.